Breadcrumb

- Home

- Learning and Research

- Debunking Myths About Lung Transplantation For PH ...

Debunking myths about lung transplantation for PH – A webinar for patients and caregivers

A Lung Transplantation in Pulmonary Hypertension Workstream webinar

25 September 2024

The PVRI Lung Transplantation in Pulmonary Hypertension Workstream presented a patient-focused webinar on debunking myths of lung transplantation. The areas covered included transplant evaluation, outcomes, and the experience of patients.

Presentations

- When do I need to think about a lung transplant? Corey Ventetuolo, Brown University, USA

- Transplant evaluation, listing and surgery Caitlin Demarest, Vanderbilt University Medical Centre, USA

- What can I expect after the transplant Nicholas Kolaitis, University of California SF, USA

- A patient’s perspective Natalia Maeva, PHA Europe and Diane Ramirez, PHA North America

Moderated by Reda Girgis, Michigan State University/Core Well Health, USA and Deborah Levine, Stanford University, USA

Full transcript

NB. This transcript can be translated into your preferred language using the button on the bottom right-hand corner of your screen.

DISCLAIMER: Despite every effort to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, we strongly encourage all visitors to consult with their healthcare professionals before making any decisions based on the information provided. Additionally, while the quality of Google Translate has improved tremendously in recent years, please remember that it is an automated service and not a human translation.

Reda Girgis (Moderator)

Welcome everyone, thank you so much for attending. My name is Reda Girgis. I am the Medical Director of Lung Transplantation at Corewell Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan and the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine. It's really a pleasure having everyone participate in this webinar, we're very excited. This is organised by the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute in collaboration with Pulmonary Hypertension Association US and Pulmonary Hypertension Association Europe.

We have several experts in the field that are going to give us an overview of this issue, and we are very excited to have two patient representatives share their perspective on this topic. I'd like to start by introducing my esteemed co-moderator, Dr Deborah Levine. She is a Professor of Medicine at Stanford University Medical School, and a world-renowned expert in the fields of both lung transplantation and Pulmonary Hypertension (PH).

Deborah Levine (Moderator)

Thank you Reda. This is wonderful that you've organised this whole thing for everyone, from clinicians to patients, to everyone who's interested in PH and transplantation. We're so excited to have wonderful speakers, and a great discussion at the end.

Let's start off the show with Dr Corey Ventetuolo. She's a PH physician and an Associate Professor at Brown University and the Associate Chief of pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine at Brown. She is going to talk about "When do I need to think about a lung transplant?"

Corey Ventetuolo (Speaker)

Thank you, Reda and Debbie, for the invitation to participate in this great webinar. Thank you to PVRI for putting it together. I'm excited to learn today, along with all of you. I'm Corey Ventetuolo. I wanted to start with a few disclosures, which informs the perspective with which I look at this and work with patients as they move towards lung transplantation evaluation.

I'm a US-based physician. So of course, some of the things I say may not apply to places around the world. And secondly, while I take care of patients as part of a PHA-accredited comprehensive care centre, I am not at a lung transplant centre. So it is frequently the case that when patients of mine are undergoing, or thinking about undergoing, lung transplant evaluations, they leave our care. And so that's sort of the perspective with which I thought about putting this talk together.

I was charged with discussing what your PH team should think about, and when to refer you to transplant, and so to do this, I think it's probably most relevant to think about what the guidelines say, and our guidelines have recently been updated. Most recently, in 2022, the European Society of Cardiology and the European Respiratory Society put out guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PH. And I'm going to come in a moment to the World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension Seventh Consensus Statement on this.

These are the highlights from this. When do guidelines recommend referral:

• Individuals who are considered intermediate-high or high risk on Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) treatment should be referred for lung transplant evaluation.

• Individuals who have progressive disease or recent hospitalisation for worsening PAH.

• The need for continuous prostacyclin analogue therapy.

• Certain types of PAH that we know are associated with poor prognosis.

• Signs of liver kidney problems because of PH as well as the symptom of coughing up blood.

Now, of course, if you're a patient, you may say I don't really understand what it means to be intermediate-high or high risk. There are some scoring systems which have been validated now to predict at least one year survival in PAH. And your PH doctors may use a variety of these scoring systems. I've put two on the slides here. One is the 2022 ESC ERS baseline risk score calculator. There are others to be used on follow up. The other is derived out of US-based data, the REVEAL 2.0 risk calculator.

And you can see here from the graphics that they incorporate a variety of tests that I think patients become very used to doing in PH, including things like 6-minute walk distance, variables from echo cardiography in terms of your right-heart function, haemodynamics or right-heart catheterisation variables, BNP or NT-proBNP which is your heart failure marker that circulates in the blood. And then the US-based calculator also incorporates some other demographic characteristics, including things like your age, your biological sex at birth, the type of PAH you have, the severity of your symptoms and signs of right-heart failure which are incorporated across all of these metrics.

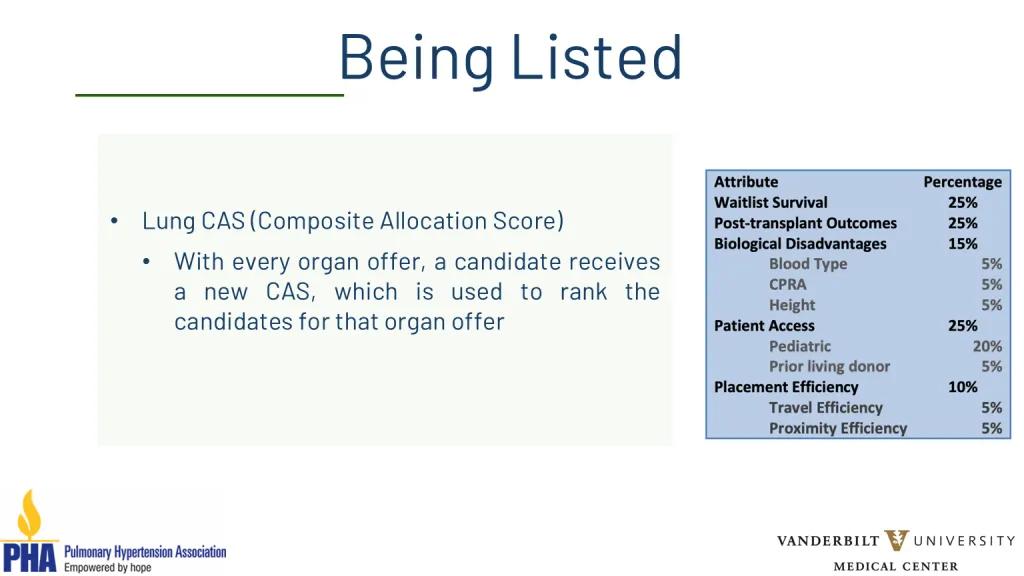

In recent years the lung composite allocation score was developed in terms of when transplant teams think about or list individuals for transplantation, and it's important to know that this has undergone some revisions, partially in response to the fact that historically, PAH patients had issues with long wait list times on the transplant list and weren't necessarily given a fair shake when they came to be evaluated for transplant.

I've listed some factors here that we think about carefully in PAH or may influence score, and those include things like mean pulmonary artery pressure, 6-minute walk distance, your pulmonary artery systolic pressure, and then, more recently, signs of right-heart dysfunction, including the cardiac index, Bilirubin and creatinine. So both the risk assessment scores that we do as part of our management of patients with PAH, as well as the composite allocation score are trying to hone in on variables that get at right-heart function, since we know that right ventricular failure is usually the path by which patients progress and do poorly with PAH.

I like this graphic, because I think it illustrates pretty well that the time before lung transplant is a really large part of the journey for an individual patient, their caregivers and their care teams. And I think there's some unique things about PAH, that the time before transplant can pose a challenge and opportunity. And those include things like additional testing that PAH centres may require as part of your evaluation for lung transplant.

Individual transplant centres vary in their comfort with transplanting PAH patients, for reasons that I think you'll hear about later in the session. And of course, I think there are some unique aspects of caregiver and support networks for PAH patients. Our patients tend to be women, they tend to be caregivers in the home, it preferentially impacts young individuals as well, and so these may influence the support networks that you need as you go through the transplant evaluation process.

I alluded to some of this on the prior slide, but some of the additional testing that you may need as part of your journey towards lung transplant includes potentially frequent right-heart catheterisations and in-depth oesophageal evaluations, particularly for patients with systemic sclerosis. If you have certain subtypes of PAH, that may mean additional testing, and these include things like scleroderma and congenital heart disease if you have liver and kidney involvement as a result of your PAH.

At the time of transplant there are careful considerations about bleeding risk. I think current changes in our treatment landscape, for example Sotatercept, may represent sort of a moving target, as we think about the transplant eligibility and population. And as I mentioned, often our patients have to contend with thinking about childcare, and other issues surrounding the home as they move towards transplant evaluation.

My colleague on the call, Dr Nicholas Kolaitis, is going to be speaking in a bit, but I think this is a really pivotal paper where he focused on the fact that updates to allocation systems, at least in the US, have evolved to include PAH and right-heart failure as a special circumstance. But despite those changes, our patients still have a high wait list mortality and low rates of transplant, despite actually very reasonable and good lung transplant outcomes. So he tried to unpack this. And I think this is now reflected in some of our updated guidelines. I mentioned the World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension. The consensus document that was just released on this made a strong sort of plea for patients to be engaged in discussions about transplant early in their treatment course, so this is part of the reason why we're doing this webinar today. And that it's important that PH programmes develop really formal referral processes, and in-depth collaboration with transplant centres. And we've done that here with good success.

I wanted to briefly mention multiple listing. I think this is important, especially given some of the challenges that I've already mentioned in PAH, so multiple listing refers to registering at two or more transplant centres. Candidates closer to the donor hospital are considered ahead of those more distant. So that is a factor when you're looking at variable transplant programmes. This may increase chances of a local offer. Priority is given by area not hospital, so if you're thinking about multiple listing, doing this in the same allocation area is unlikely to help.

Waiting time is not considered as part of the lung transplant priority list. So that's not a factor here. You have to still meet criteria of the individual centre, and those criteria can vary, particularly I think, in PAH as I mentioned. Your insurance provider may or may not cover these additional evaluations. And you have to think carefully about travel and lodging before and after transplant. I think it's important that you, as a patient or caregiver, choose centres carefully, and there is publicly available information on this. This is from the scientific registry of transplant recipients. You can plug in a specific programme and find out how frequently they've done transplants, what their survival on the waitlist looks like, what their one-year survival statistics look like as compared to other centres.

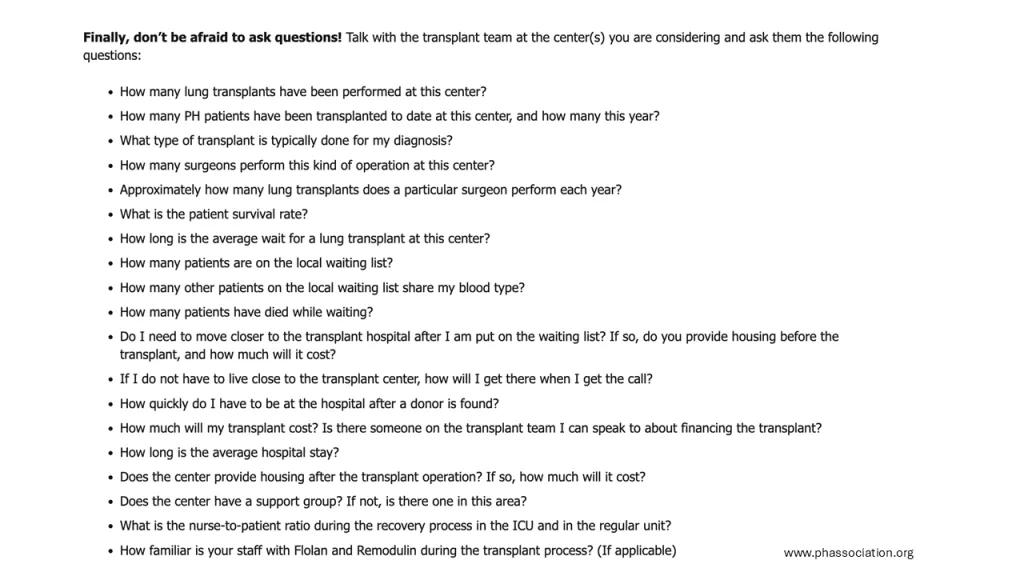

This is from PHA:

And I think these are great questions to think about asking your transplant team at the

centres that you're working with, you know I would not be afraid to ask:

• How many lung transplants have you performed, specifically in PH patients?

• What is your comfort level transplanting PH patients?

• What are the expectations of me and my support system after I'm transplanted, or while I'm transplanted in terms of being located locally, for example.

And then, finally, I just wanted to say that you know you're not alone. And going through this process there are many organisations, PVRI included, PHAs around the world, and some of these other websites that I've listed here:

There of course are local support groups, individual patient connections that you make. We do this all the time. At my centre, we connect patients who have already gone through the transplant process with patients who are just starting on their journey. There are PH and transplant centre resources, and of course, the National Societies I just mentioned. And with that I just wanted to say thank you very much, and I look forward to hearing the rest of the speakers and the discussion today.

Reda Girgis (Moderator)

Thank you, Corey. That was a fantastic presentation. I'm sure that's going to generate a lot of discussion. As mentioned, we'll have plenty of time hopefully for Q&A at the end, and then we can take questions so the whole panel can take the questions then, and also if you have questions, feel free to put them in the chat, and we'll get to those.

It's my distinct privilege to introduce our next speaker, Dr Caitlin Demarest. Dr Demarest is the Assistant Professor at the Department of Thoracic Surgery at Vanderbilt University, where she's also the associate Surgical Director of Lung Transplantation, and the Associate Program Director of the Thoracic Surgery Residency and the co-director of the laboratory for organ recovery, regeneration and replacement. She's an experienced lung transplant surgeon at a very esteemed program at Vanderbilt and she's going to tell us about the transplant evaluation process and listing and surgery.

Caitlin Demarest (Speaker)

Thank you for having me, I’m excited to be here. So as mentioned, I'm one of the lung transplant surgeons at Vanderbilt. We do a good amount of transplants, 95 last year, and on track to do about the same this year, which is a large programme. We take a lot of PH patients preoperatively and support them through transplant and get them through transplant. It's one of our areas of interest and expertise and my laboratory that I co run is focused on also PH patients and improving their support.

When I was asked to give this talk, I really just tried to think of things I would want to know from your perspective, you meaning patients, and what could I expect with a lung transplant? So I'm going to try to go over some of those things and hopefully just shed a little bit of light on what it's like to go through the surgery.

For those of you that have gone through the transplant process, or the evaluation process, or are going to, it is very daunting. There is a lot of testing that is needed. Often, if you go to a different centre, we have to repeat the testing and it just depends. A lot of this depends on centre preference. This also depends on surgeon preference. Some of us like certain evaluations or testing done on our patients. Things that we care about from the surgeon’s perspective include the CT scan which can be very telling, because our job primarily is to determine if it is safe to do a lung transplant on you.

I explain to my patients that there are all these different teams. Everybody gets their vote: the pulmonologist gets their vote, the psychiatrist gets their vote, the social worker gets their vote, and the surgeon gets their vote. And I need to figure out the things I care about to get my vote on whether you're an appropriate patient to have a lung transplant. And so some of the things I care about are the CT scan, can I physically do a lung transplant on you, or do you have some kind of anatomical problem that would prevent me from doing that. Also somebody with PH, we really care about the echo of the heart, and how well the heart is working, and the right-heart catheterisation, which gives us a lot of information about the blood pressure levels in the heart, which affects the way that we proceed with the transplant and a lot of our decision making.

When you're getting ready for the lung transplant surgery itself, it's like training for a marathon. You want to be as strong as you can. A lung transplant is a really big deal, it's a massive operation and you need to be as fit as you can. Rehabilitation or prehabilitation before the surgery is very important. You should be in pulmonary rehab, even if not, you should be walking as much as you can every day just to try to stay as fit as you can. We often encourage weight loss - every programme has its own cut off for BMI. And that just depends on the programmes criteria and the surgeons comfort level. If people are obese, they have decreased outcomes of lung transplant, and that's why we're pretty strict about it. But different centres have different cutoffs. Based on like I said, their comfort level. But we always encourage weight loss before surgery.

Then once you're listed you are assigned a Composite Allocation Score, a CAS. And this score looks at all these different variables and gives you a number, and that number then puts you on the list at a certain priority level, and you are kind of matched with each donor and assigned a CAS, so your CAS can be 20, it can be 60, it depends on all these variables listed here, and that's kind of how you're prioritised for each donor.

And so they find a lung donor, and they go to the list, and they go nationally and look at who ranks number 1,2,3,4 and they just go down that list and ask each surgeon if they're interested in the organ, and that's how that works. And so once you're listed, you just hang out with your phone on you at all times, hoping and waiting for a lung offer. And a coordinator or somebody from a programme will call you and say we found some lungs for you, it’s super exciting, why don't you come to the hospital.

So generally, with most programmes, you would then go to the hospital and get admitted and wait for the transplant. In the meantime all this other stuff happens. The surgeon and the team are working with the donor hospital to facilitate the logistics of this. So let's say I have a donor in Alaska. I have to fly my entire team to Alaska, and also all the people from different organ systems have to coordinate - the heart team, liver team, lung team, to be there at the same time to do the organ procurement for the donor. So a lot of logistics go into it. You'll come to the hospital. They will tell you we have a lung transplant for you hopefully tonight at like 5pm. It's not going to happen then, they never happen on time because of all those logistics I mentioned.

And occasionally, once the team gets there to evaluate the lungs, they find something that makes the lungs not usable. They find pneumonia or a nodule or something, and they call the surgeon and say, I don't know, these lungs aren't so good. And then we tell you, sorry you have to go home, we'll call you back and find a better set for you. Most of us refer to that as a dry run and some programmes have more than others, just depending on how aggressive you are. But that's just something to be aware of.

And then, while you're on the list, you've now gotten ready and got approved for your transplant. But now you have to stay ready, so you have to continue to lose weight if that's what you're being instructed to do, you have to continue with rehab whether it's on your own or pulmonary rehab. You have to be nutritionally optimised. Obviously, the stronger you are the better you're going to do, and so you may be required to take supplements, protein drinks. Some patients who are particularly malnourished need a feeding tube placement before surgery to get you as nutritionally optimised as we can before the surgery. And that just depends on the patient and your health.

So most patients with PH get a lung transplant, a bilateral lung transplant. Generally, with very few exceptions, do people with PH get single lung transplants. And sometimes, if the heart is irreversibly injured due to the PH, then a heart lung transplant is offered where you do the heart and the lung - that is less common, but it's sometimes required.

Now I’ll look a little bit at the basics, but also the nitty gritty of surgery itself. So you get called for your lung transplant, you go to the operating room and generally the anaesthesiologist puts you to sleep. For patients that have PH, I often tell the family that this part, the actual going to sleep part, can be the most dangerous part of the operation, because you're very tenuous when you have pulmonary hypertension. And so we have to be very careful when we do that. So oftentimes depending on how sick you are and how bad your PH is, we will put catheters and wires and big IVs in your groins or in your neck while you're awake, just to keep you stable during the going to sleep part.

ECMO, if you're not familiar, is an artificial heart and lung machine that we often attach patients to, and we may even do that while you're awake before the surgery. The anaesthesiologist will put in the transoesophageal echo down your oesophagus, and that helps us evaluate the heart function during surgery, which just ultimately is what helps to keep you safe.

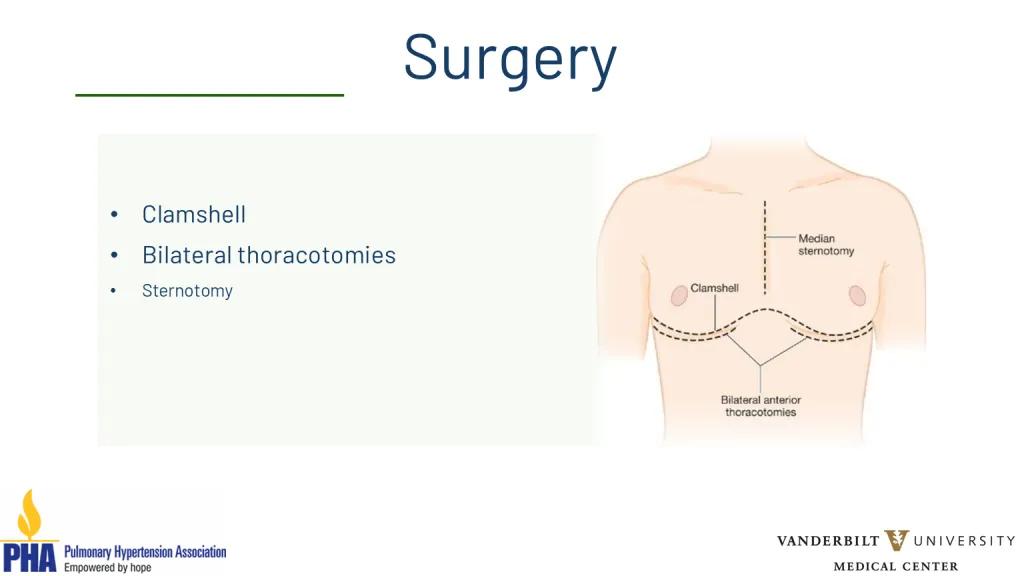

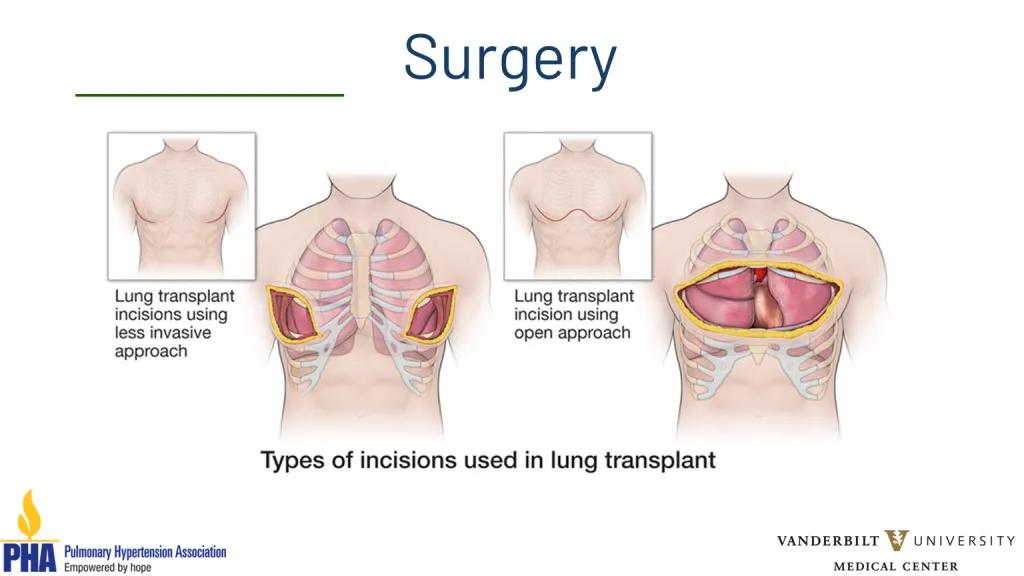

So then you're safely asleep. We prep drape you just like you see in the movies. And then we make our incision. So there's various types of incisions for a lung transplant.

A sternotomy is down the centre, you see there, and then there's a clamshell which goes all the way across the chest, and then there's bilateral thoracotomies. With the exception of a couple of programmes, most people don't do a sternotomy. I would say the vast majority of people in the world do either clamshell or bilateral thoracotomies.

Thoracotomies are just kind of like each side of the clamshell without connecting the middle. And so that's basically the surgeon’s preference. My personal preference is, I start with the bilateral thoracotomies just under the breast, and then depending on how well I can see inside your chest, and how much room there is - if your heart is very, very big, it's hard to see very well. So then we go across the middle as a full clamshell.

Here's an example of the difference between the thoracotomies and the clamshell:

And again, it's just kind of based on your ability to see - all that matters is doing it safely right? So I prefer to not go across the breast phone when I can. But I just need to do it in a safe way. So whatever we need to do is what we do.

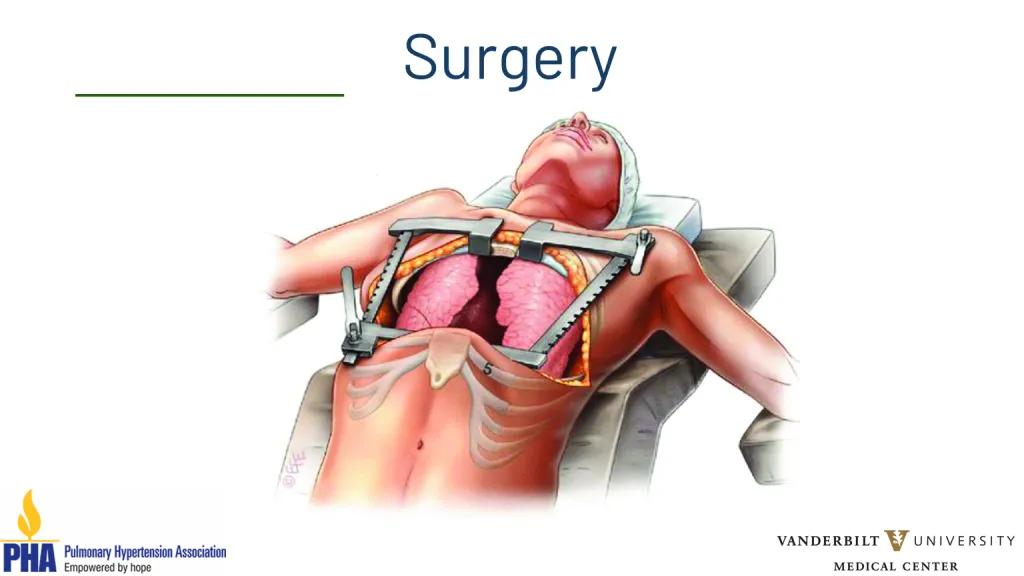

And here's an example of a clam shell.

It looks exactly like this. Put the two retractors just like you see there on each side and open the chest fully, kind of like opening the hood of a car. And you see the heart and the lung, you have full access to everything in the chest.

And then the surgery - you remove the old lungs and sew the new lungs in. This is actually the easy part. So there's 6 anastomosis, three things on each side. You sew an artery, a vein and a bronchus. The surgery can take anywhere from 7 to 12 hours. It just kind of depends, sometimes less than that. But it is just very, very variable, and a lot of that depends on how stable you are, how sick you are, if there is any scar tissue on the inside, if you had prior surgeries - that could take us some extra time. But it just depends. The goal is just obviously to do it safely.

I'll briefly mention ECMO, because it's important for patients that have PH to have a little bit of an understanding. So ECMO, as I mentioned, is this machine that functions like an artificial heart and lung. It’s very complicated but there are various ways to connect this device to a patient to provide oxygen and or heart support. We use this sometimes in patients pre-operatively with PH and other conditions such as COPD, but especially in PH, we can use this device to support you preoperatively, to help you survive into a transplant if you get sick. There are only some centres that have very broad experience with this or that would offer this, but it is something that is considered for every patient in a pre-operative setting.

Most of us in the world also use ECMO in the operating room just to keep you safe and stable while we're doing the lung transplant, and then post operatively, for patients of PH it is fairly common to keep patients on ECMO after the surgery. This is because your heart has had to pump really hard into your diseased lungs, and now you have these nice healthy lungs, and your heart is still used to pumping hard so if your heart pumps too hard into your new fragile lungs, it could damage them a little bit. So many people believe that all patients of PH should be put on ECMO post op. Others do it kind of selectively. I do, kind of selectively, but it's just something to be aware of that this could potentially be in your future. And it's something that we are very used to, and good at managing.

So now surgery's over, and it went great. You will have tubes and lines everywhere. You will have chest tubes on both sides, depending on the surgeon, and we'll determine how many you have. I put two on each side. For the goals, the first day or so post-surgery are to work on your pain control. There are various things to accomplish this. Some people get epidurals. We do that generally. At Vanderbilt we also do intercostal cryoablation, which is this procedure that freezes the nerves in between your ribs that helps the pain as it kind of numbs everything.

And then we work on anxiety – people can get very anxious having the breathing tube. And so we work on the pain control and the anxiety, and working on getting the breathing tube out. Once the breathing tube comes out hopefully then we're working on just getting you up and moving. You want to be out of the bed, working at physical therapy. It's so true that the patients who are more motivated do better. You have to be motivated, and you have to be aggressive about getting up and pushing yourself and working really hard. And I always tell the patients after surgery, that I did my hard part. Now you have the hard job, you have to get up and move and walk. If you've had a clamshell, the physical therapist will be seeing you to help you get stronger. If you've had a clamshell or a sternotomy where we went across your breast the physical therapist will teach you things that you need to do to avoid stress on those wires and the plates that have put you back together.

Nutrition is very important. We are very protective of our new lungs, and so we can't let things go down the wrong pipe into the new lungs. So we are very careful to make sure you can swallow in a safe way, and until then you get a feeding tube. But I think almost everybody at all centres puts this little tube in, and that provides nutrition until you're able to take enough orally. And for some people, for example, your oesophagus or your stomach is lazy, so then you get a feeding tube in your abdomen. And in some patients, rarely, but for some patients that could be forever. You're committing to having your new lungs, and we will protect them above all else. And so it's something just to be aware of.

And then the whole team would be working on educating you about your lung transplant. Of course there's always little hiccups. Things are heading in the right direction, but there's always little things that come up. Potential things that can happen are post-operative bleeding, problems with any of the new connections, the airway that we sewed together can have issues healing because the blood supply to it is not great. You can have infection, you can have rejection, you could need a feeding tube longer term. You can have lazy lungs that take a little time to wake up. You might need ECMO for a few days, need a temporary tracheostomy. But for the most part you can overcome all of these, and we have ways to treat all of them. And generally we can get through whatever comes up, we can kind of get through it.

And then you go home, and post discharge is rehab, rehab, rehab. You will be working hard, going to physical therapy, continuing external precautions to protect the bone, the cuts in the bone if we have made any. You may or may not go home with a chest tube you'll have to care of. But again, we'll teach you all of that and teach you how to take care of your incision. And then you have your post op visit with the surgeon, and generally that's the conclusion of your relationship with the surgeon. You see the pulmonologist forever and ever. But that usually concludes your relationship with a surgeon. Thank you guys for having me, I hope you're more enlightened than before.

Debbie Levine (Moderator)

Thank you so much, Caitlin. That was great. I think we're going to do questions after - I see Pamela had a question for you, Caitlin. So maybe you'll answer that after the end of the talks, but that was fantastic. Really so educational for all of us.

The next talk is about after the patient leaves the hospital. You know what happens to our patients, you know they go home. What is the post operative course? Not just the post operative course, but what happens after a lung transplant when you go home. You're visiting a clinic. What is that period like? Which really is a very long period. Usually for the rest of your life.

So we have Dr Nicholas Kolaitis, who is an Assistant Clinical Professor at UCSF University of California San Francisco. He focuses clinically on lung transplantation and pulmonary hypertension, and he is interested in improving access to transplant for patients with PAH. We look forward to having you give your talk about what can I expect after I go home after lung transplant. Thank you.

Nicholas Kolaitis (Speaker)

Well, thank you to the PVRI for organising, and to Dr Levine and Dr Girgis for moderating and organising this session. The goals that I have for today are:

• To discuss the care of the patients after lung transplantation.

• To discuss the impact of lung transplant on quality of life and other patient reported outcomes.

• And to discuss the impact of transplant on survival.

We'll talk about post-transplant care, and this is the timeline that we typically have for patients at our centre at UCSF:

• 2-3 weeks in hospital

• 6 weeks in a hotel

• Forever at home

This might vary a little bit, depending on whichever centre you're being evaluated at. But most patients at UCSF will stay in the hospital for somewhere between 2 to 3 weeks. And then we ask them to stay in San Francisco or the immediate surrounding area for 6 weeks in their recovery period to make sure that if there are any issues they're close by, and we can help take care of them. And then the goal is that they stay home forever, and they never need to come back to the hospital.

And so what can you expect? So again, that first period of time when you've left the hospital is different, based on the centre that you're at. At UCSF everybody stays in San Francisco for six weeks. And we typically will do a clinic with patients every week. We ask them to get their labs drawn twice a week, and during this period of time we do around two to three bronchoscopies. Typically a bronchoscopy is where we take a camera and look inside the lungs and take some biopsies. This is done at two weeks, one month, and two months post-transplant.

We also do ultrasounds of their extremities to make sure that they haven't developed blood clots. We'll refer them to rehabilitation, have them see a nutritionist. And the other thing is that we require patients to have two adult caregivers that are available for them. They need to have at least one caregiver with them at all times during this six-week period of time. And the reason that we have this caregiver requirement is, and throughout the course of the talk you'll hear some statements that are ones my patients have heard me say, in that taking a transplant patient home is like taking home a baby. I have a three-year-old, this is her, and for those of you that are parents you remember how challenging it is at that first few weeks when you bring home that child. Taking home a transplant patient is similar. And this is why we require adult caregivers to help take care of patients. Because there's a lot of complexity.

And so what is the complexity in the first few weeks? Well, there's a huge pill burden. Patients need to focus on rehabilitation. They have pain from their incision that limits their mobility, and limits their ability to take other meds. Because sometimes the pain meds can interact with other things. And then there's a whole sense of mental health issues that develop after transplant. Where patients are getting over the stress of facing their death. And then readapting to their new life after transplant.

Another statement that you'll hear me make to my patients is that upon discharge, your job is to get home, sit down and take your medicine. That's it. Nothing else. And the reason is that the medications are really your lifeline after transportation. We give each of our patients a card which has a list of their medicines. This is the first side of the card, there are two sides. And typically, we have patients on three immunosuppressant agents. You can see here that one of them is called Prednisone. And this is a medication that can cause people’s bones to get thin, can cause high blood pressure, can cause agitation. A medicine called Cellcept, which includes some gastrointestinal problems, and a medicine called Prograf, where we have to monitor the levels really closely. And this is the reason why we have to take the labs initially twice a week when they're in the recovery period.

Now, in addition to that, if you look at other centres, and this is data from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, we're not the only ones that practice in a similar manner. If you look at patients one year post transplant across the ISHLT registry, you see that the vast majority of patients are on Prednisone plus Tacrolimus, and this medicine Cellcept.

In addition to these immunosuppressants, patients are on other medicines. Medicines to prevent infections like fungus and bacteria, as well as medicines to prevent the metabolic complications of transplantation, the medicines to protect your bones, medicine to prevent high cholesterol, medicines for high blood sugars that patients can develop after transplant, medicines for high blood pressure that can develop after transplant. And this is all in addition to your existing medicine. The patients are oftentimes on 15 to 20 different medicines after their lung transplantation.

Additionally, we do procedures called bronchoscopies, where we take this camera, we look inside the lungs, we put some fluid down there, suck the fluid back out, and we take biopsies of the lung tissue to look for rejection. As I mentioned at UCSF, in the first six-week period when patients are recovering, we do about two to three of these bronchoscopies. And then we do more after they leave the hospital.

So what happens after you go home? So after that six-week period, which again might vary depending on the centre that you're at, we typically will see patients once a month between months two through six, then every other month, between six months through one year. And then we see patients every three months for life, and some of these are over video so it is a little bit easier for patients. But at the very least we're seeing patients in-person once every six months.

The bronchoscopy schedule differs by centre as well. Some centres only do bronchoscopies for cause. We are a centre that does bronchoscopies as surveillance. So, as I mentioned, in the first six weeks you're typically getting two to three of these, but then we'll also perform bronchoscopies at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months. The lab testing spaces out. Once people leave San Francisco, it's initially once a week, and then it's monthly for life.

And so transplant is hard, and it's challenging, and it requires a lot of work. So the other statement that you'll often hear me say to my patients is that transplant is trading one disease for another. But the reason the patients will take this trade, and the reason that patients do this, and the reason that I do this with my life is because transplant works.

So this is the patient's lung function after transplant. Patients with PH in particular don't have this drop in lung function before transplant, but this is a patient with Pulmonary Fibrosis. They got transplanted, and you see that their lung function improves dramatically after the transplant, and then it stays at that level well after the transplant, so patients can do really, really well after transplant.

And so that gets me to the point of why we do this. And we do this really to fix 2 problems. And so the two primary aims of lung transplantation are:

1. to improve a patient's survival.

2. to improve their quality of life.

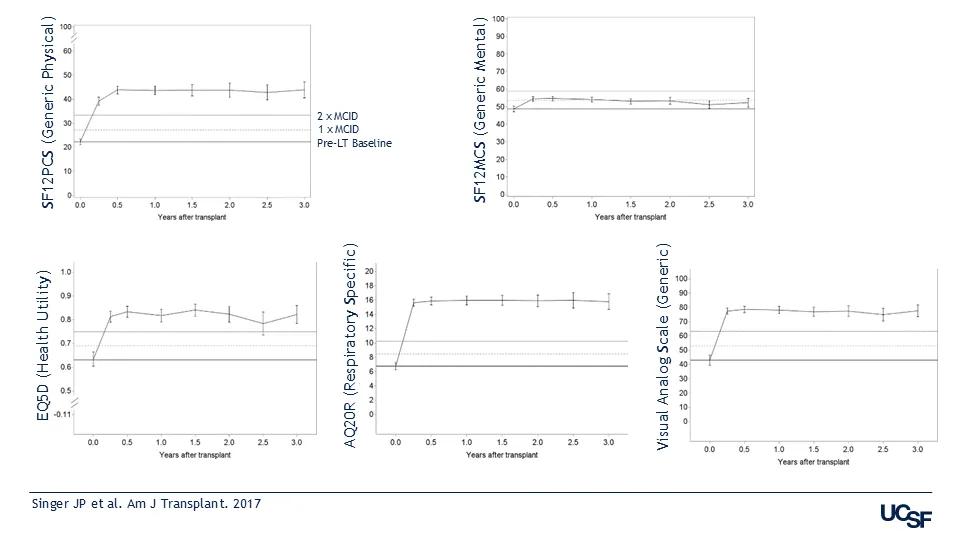

And so transplant is successful in both of these aims, and for that reason the trade of the PH for the transplant is often worth it for many, many patients. And so how does transplant work for those two aims? First, we'll talk about quality of life. So this is data from our centre, looking at quality of life. And what you'll see is a series of panels here.

What you'll see on the chart on the top left is the X axis which is years after transplant and on the Y axis is the score. And so this is a generic physical quality of life measure. These are all comers to our centre that had a transplant. The first line right here is the baseline (Pre-Lt baseline), and then the second line is the minimally important difference (MCI). So that means that an improvement from the Pre-Lt line to 1 x MCI line is clinically important, and you can see that physical quality of life improves by about three times the clinically significant threshold.

We see mental quality of life improve at the level of the clinically significant threshold. We also see a generic health utility instrument improve around 2 and a half times the clinically relevant threshold. We also see a respiratory specific, so a breathing specific, quality of life metric improve by around four times the clinically relevant threshold. And you see another generic measure improved by about three times so quality of life improves a variety of different measures after lung transplantation.

Dr Demarest talked a little bit about use of ECMO and patients with transplant before the transplant. In particular, patients with PH might get so sick that they need ECMO before the transplant. And so we also looked at those patients who underwent ECMO prior to transplantation. You see that the improvement in their quality of life was just as good as patients that came in from home. So even patients that are so sick that they need to be on a heart lung bypass machine going into the transplant will have dramatic improvements in their quality of life.

What about if you get really sick after the transplant? So one of the things that was alluded to is that sometimes we'll leave patients on ECMO after the transplant, because patients with PH are at an increased risk of injury to their lung right after the transplant. You can see that patients with bad lung injury right after the transplant still have dramatic improvements in their quality of life once they actually make it out of the hospital. So even if you get really sick before the transplant, and even if you get really sick in the recovery period after transplant, your quality of life still improves dramatically.

What about frailty? Frailty is the idea that two people that could be the same biologic age might be very different in terms of their physiologic age. So you can have two gentlemen that are the same biologic age. And one is weak and in a wheelchair, and the other is a body builder, and he's quite strong. And so transplant impacts these outcomes and frailty also impacts transplant. So the presence of frailty before a lung transplant is actually a bad thing, and it's associated with lower likelihood of actually making it to transplant. Patients that are frail going into the transplant are less likely to survive to the transplant. And this is one of the reasons why Dr Demarest mentioned that it's important to stay active and rehabilitating before the transplant.

In addition to that, being frail going into the transplant is associated with worse outcomes after the transplant. So patients that are frail before the transplant are more likely to have a mortality event, so they're less likely to survive to a year post-transplant than those that are not frail going into the transplant. So all the more reason to try to stay fit and strong, going into the transfer. This being said, frailty actually improves after transplantation. This is a really interesting study that was done looking at frailty before and after transplant, and showed that patients’ frailty scores actually got better after the transplant. Not all frail patients will remain frail after transplant, and actually fixing the lung disease can help fix the frailty as well. So if somebody is frail going into the transplant, it doesn't mean that they're not a transplant candidate. It just means we need to do everything we can to ensure that they have a good outcome after the transplant.

What about depressive symptoms? Depression is something that many patients with chronic lung disease suffer from. And depressive scores get dramatically better after transplant. You can see around two times the minimally clinically important difference. And if you follow the trajectory of depressive patients before and after transplant on the right panel here you see the pre-transplant baseline. Actually, most patients go into the not depressed category after the transplant. So transplant can actually improve depression symptoms after transplantation.

Finally, I'll talk about survival. So patients post-transplant can have limited survival from various reasons. Early on the biggest risk is graft failure. So this is primary graft dysfunction, where the lung doesn't work initially after the transplant. We see infection sort of in the mid-range. When patients get further out from transplant the things that they might pass away from are cardiovascular disease, malignancies as well as the development of chronic type rejection in their lungs.

If you look at survival after transportation across the board. So this is data from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Median survival, meaning 50% of patients on transplantation, are alive at around seven and a half years post-transplant. And if you stratify by diagnosis, you see this interesting thing. The patients with PH are here, and you see that early on many of them have a problem with survival. So many of them actually don't make it past the first-year post-transplant. This is historical data. And the reason for this is likely from that lung injury that happens right after the transplant. But if you follow a patient long term with PH, you see something interesting that they actually do really, really, really well long term, and they have the second-best long-term survival. And if a patient can actually make it past the first-year post-transplant they actually have essentially the best survival post-transplant.

So this is data going back to 1992. But we've gotten better at treating these patients. And we've gotten better at transplanting patients with PH. If you look at our internal centre at UCSF, for example, you see that our median survival at UCSF is around 11 years post-transplant. And our 5-year survival in the most contemporary area is around 83%. And when you look at patients with PH, you compare them to those without PH, you actually see the same survival of those with PH and those without. And so we've gotten better at treating patients with PH. We've gotten better at getting them through the transplant and so, if you're looking to be transplanted, make sure that you're being evaluated with expertise in transplanting patients with PH. With that I'll stop and say thank you.

Reda Girgis (Moderator)

Excellent presentation Nick, thank you so much. That was so informative. So we've now had 3 talks by expert clinicians in the field. And now we're going to turn it over to get a patient's perspective on this process. And we're really honoured to have a representative from the Pulmonary Hypertension Association in Europe as well as a representative from Pulmonary Hypertension Association in the US.

So I will hand it over first to Natalia Maeva, and she is a lung transplant recipient with a history of PH, and we are looking forward to hearing her perspective and share her thoughts with us.

Natalia Maeva (Speaker)

Thank you so much. It's a great honour to be part of this session. I was transplanted eight years ago in a transplant centre in Vienna. In my country, Bulgaria, we didn't have a programme for lung transplantation, so I was not able to receive the proper treatment before the transplantation. Also, I didn't have any access to rehabilitation before my transplantation.

I will speak about the myths surrounding the lung transplantation during the first year after the lung transplantation. First of all, in my personal view, it was that I will be able to walk three days after the surgery. But the mission was impossible. And I can say that for the first months after my transplantation, the recovery was very, very hard.

As we learnt from the presentations before me, the transplantation is a huge surgery. The recovery takes a long time. In my case it was about three months. And for me it was a very, very hard period because I didn't get rehabilitation before the operation. This is me during my recovery process in Vienna after the transplantation. I'm very thankful for the efforts of the team of Vienna Hospital. After three months I was able to walk normally, even though I was only 43kg.

You can imagine how hard it is - the full recovery after the transplantation takes months. In some cases, patients need more than one year to become normal. The biggest problem also is a fear to breathe normally, because before the transplantation, all the patients with PH use oxygen, and when you wake up, and when you saw your situation, it's so high, it's unbelievable to see the numbers. But you are afraid to breathe. And also it's very important to learn that you need time. In my case I forget to breathe normally for seven years. So it was a very big challenge.

The second myth that I would like to share is that rejection is a sign of failure. Because after the transplantation usually the doctors prepare you for the possibility that rejection can happen. But the immunosuppressive medication can help to manage the rejection process. So my message to all patients is, don't be afraid if you have rejection because now we have many different algorithms to solve this problem. I have friends who have had a few rejections. They are still in very good condition. So it depends on the doctor teams, and we must believe the doctors.

The third myth is that medication side effects are overwhelming. The fact is there are side effects using the immunosuppressants. Usually women have a very big problem with weight because in the first six months you are crazy to eat sweets - it's about the cortisone. All of you know the high doses of cortisone. Also during the first year, the doses of immunosuppressants slowly go down. So the patient can accept this inconvenience and go ahead. Every patient has a personal plan. It's very strict, so it's normal to share with other patients. How many grams, for example, you take of Prograf.

It's different for everyone. In my case, I think 8 months after the operation, I started to realise that I can go ahead. In the beginning I was afraid of an hallucination that I had. This affects the patients and it's very important for the team of the clinic where the operation was performed to have the physicians and psychologists who can help you get back to normal, to help you realise that you just saw something in your head. But it's not real. For example, in my case, for three days I was travelling in Canada. I never been in Canada. But the medical teams were wondering why I'm speaking about Canada and a very nice lake. But after that they solved this problem. So let's hope that someday I will visit Canada to see this lake.

The fourth myth is that you will be on a restricted diet forever. No, this is not true. Because after the first year you can get back to normal weight, and you can eat the things that you love, including products that don’t interfere with your therapy. For me it's a big problem, because I come from a country where the cheese and yoghurts are well known. So it's a little bit complicated, but I learn to live without this. It's a personal responsibility to the donor because you have received a part, you must be very, very careful when you have it. In my case, I was waiting eleven months for my new lungs.

And the fifth myth is that you can’t live an active life after the transplantation. It is not true. You can see here some photos of me. In July I was part of the Bulgarian transplant team and we attended the European championship for transplanted patients, and I became a European champion in my category of 50-59 years. And you can see the gold medal went to the chief of my team in Vienna, Prof. Shahrokh Taghavi who made the impossible possible.

It is very important to create supportive networks between the patient organisations. Also to give our experience to the families where there are patients waiting for the transplantation. Also, the biggest problem in my country is that we didn't have a programme of what is necessary before the transplantation and after the transplantation. So in all my networks now I'm trying to share my experience with people who are waiting for lung transplantation.

In conclusion, lung transplantation offers a new, active life for many individuals. We must avoid the myths. The biggest gift of life is the donation and transplantation. Because when you decide to make such a gift to the family where one is needed, for example, heart or lungs, this part will live forever in the other body. So this is the biggest gift in human life.

Thank you for your attention. I wanted to share this great painting of Michelangelo which has a secret meaning for me. You can see the message of God, and Adam, and you see between the two fingers there's a little bit of empty space. This empty space is our trust that the donor, donations and organ donations and transplantations save lives. Thank you so much.

Deborah Levine (Moderator)

I think both of us wanted to get in there and say that that was just beautiful. I think in the way you communicated your myths they are so much more powerful coming from you than it would be from us. And what a beautiful story! And congratulations on your gold medal and the whole team. But that was absolutely beautiful, and I think it was a gift, and I think we have one more gift coming from Diane Ramirez, who is a patient as well, and is an advocate of the Pulmonary Hypertension Association of the US. And we can't wait to hear your story as well. These are so outstanding to hear. Thank you.

Diane Ramirez (Speaker)

Thanks. Hi, everyone. I'm really, really thankful to be here and thankful for this webinar happening, and hopefully we're helping a lot of people out there today to understand the transplant process.

I'm going to talk about a little bit about early referral that was mentioned earlier. And yes, we talk about improved patient outcomes in the medical aspect. And I'm going to talk to you about coming from a patient aspect, and my decision had to be made on the fly. The decision was made, and I was listed for a heart lung transplant within five months. And that is not a lot of time. I went through the initial evaluation and then had a follow up evaluation and got the phone call from the committee that I had been accepted, and that not only did I need a lung transplant, I needed heart and lungs. And then I had to get to the hospital as soon as possible.

For us to get there we had to relocate, we had to do a fundraiser. My husband had to speak to his boss in human resources about his job. I had to get caregivers, they had to sign caregiving contracts with the hospital and set up everything for rehab. It was a lot of work, and it was a lot to process. And all of this was happening at the same time as I was trying to process that my life was ending, and it was never going to be the same. That the only thing that I could do was to go forward with the transplant.

So it's a lot to do at one time. Emotionally and spiritually, it is a heavy load, and then you've got all the external stuff happening - talking to family and friends, setting up moving, finding a place to live. So as a patient, if you are presented with the possibility of transplant, if you can learn about it, and a referral is set up, absorb the information and try to get used to that part as much as you can. It will help you in the long run prepare for the rest of it.

My life is completely different, it's absolutely fantastic. I had a transplant last year, and I'm doing incredibly well. I'm very active and involved with PHA and transplants. I work with other patients and other people in the medical community to improve it for patients with PH and transplants. I just want to let you know that transplant is very complicated, there is a lot to it. I'm an experienced patient. I had PH for 36 years. I have been involved with the PH Association for, you know, I want to say too long. It's been a long time, and I thought I knew a lot about transplants. And when I got to the evaluation, I realised that I didn't know anything. It is a huge topic. So whatever you can learn as a patient and absorb and break it down, it's going to help you in the long run, and it doesn't have to be something that you're terrified of. It doesn't have to be the big bad monster in the corner that you tried to avoid. It can be a sign of hope. It can be a sign of a new life. It could be a sign of a completely different life.

I had PH for so long, I got used to having limitations. Now I have to get used to not having limitations, and there are days where I don't know how to handle it, because I have so much energy, and I can do so many different things. And you know, I'm afraid I'm going to push the envelope. That's kind of where I excel, at pushing the envelope. So I'm still learning different things about the way my body operates today, and it has been a fantastic journey.

Have I had issues? Yes - infections, PICC lines, bronchoscopies, cardiac catheters. You name it. I have been through it this past year. That's part of it. I made the decision to have the transplant and everything that comes with it. That was my mantra. While I waited, I was on the list for four and a half months, and it was a lot of testing, the transplant clinic, the PH clinic, rehab, it was a lot of work, and I had to keep reminding myself this is the decision. This is part of it. Just to get through.

I'm so grateful that everything worked out the way it did and that I'm here today and I'm going to keep it really short, because I see we have some questions. But just to let you know if you can, get there sooner, and for any physicians that are listening to this - please don't delay with your patients. The emotional, psychological, spiritual aspect is just as important as the medical aspect. When you want to improve patient outcomes, we want to improve the entire patient outcome. That's my view of it. I'm just a patient saying that. So if I can process one piece at a time, it's always easier than having to do the entire thing all at one shot. It worked out for me. It worked out for my caregivers. It was a lot of work. We had a lot to learn, a lot of paperwork, and many, many conversations to prepare for this journey. You know, I think with a little more time it would have been easier for everyone involved. I still have to go to the transplant clinic on a regular basis. And it's okay. It's part of it. And I'm doing okay, so I'm just going to leave it there, that way we can get to some of the Q and A. But if anybody else has anything to add, or any questions for me. Please feel free. Thank you.

Reda Girgis (Moderator)

Fantastic. Thank you, Diane. Before we get to the questions, I would just like to take the opportunity to thank all the panellists and the speakers and I can tell you for sure that I learned a lot. I think this is a great example of how pictures can speak a thousand words, and we've talked about the outcomes after lung transplant, and nothing better than to see the two of you having done so well - Diane, after a year, Natalia, after eight years.

You know we've proven Nick's point that outcomes are good after lung transplant. There is great potential for very good, not only very good, but long-term outcomes. And we've learned that it is a difficult process. But seeing how both of you got through it with - your dedication and determination, and your spirit is so heartwarming and encouraging to all of us.

And I want to thank you, Diane, for asking PH physicians to think about transplant early. This is one of our main objectives of this workstream, lung transplantation for PH through the PVRI, and we want to really get the message out that transplant is an important option for your patients. And the early referrals are a good thing. It doesn't mean that you need to get transplanted now, but we don't want to be in a situation where we're trying to scramble to get you on the list, as in the case for Diane.

Deborah Levine (Moderator)

I think I echo everything. All the speakers were fantastic and having you both, Natalia and Diane, it really got to all of us. It's why we do it, all of us. I do want to say one thing about the early evaluation discussion. And I think that's one thing, when we had a group of patients that we all worked together with at the World Symposium on PH, is that one thing that was very difficult and challenging to hear is referral to lung transplant. I think the nomenclature and the language is something we have to change, and having it be more of a discussion and education about transplant. And I think that not only between PH physicians and transplant physicians, but also between patients and PH doctors, and patients and transplant physicians. And really this discussion should be happening very early, but it doesn't mean you're right there, ready for transplant. I think one thing we want to want work through is how we can maybe change the culture of the discussion, of making it more of an education for patients. More than, hey, you're going to go to the transplant centre, you're going to get a transplant tomorrow. This is all very scary. But if we can change our culture, and how we as a community view transplant for PH patients, I think for everyone on every single side of our community it will be a lot easier, and probably a lot more seamless.

Question and Answer session

Question

How long does the dietary restriction remain, like for fruits and salads, and also return to work and travel restrictions.

Nicholas Kolaitis

I think it depends on every centre. In the early period, for 6=six months, we typically recommend people avoid any high-risk foods. We don't really tell them to not eat any salad early on. But raw fruits, and raw vegetables, especially if they're not washed, we tell them to be a little bit more cautious with. And certainly eating cooked vegetables is totally fine. The restrictions that we keep people on for life are things like sushi where it's raw fish. Those would be things that we would be a little bit more careful with, and then grapefruit juice can interact with some of the medicine, so we will keep people off that one as well.

For returning to work, typically, our centre tells people that we don't want them to work for six months post-transplant so that they can get through the recovery. But if there's an extenuating circumstance and someone needs to go to work earlier because of financial limitations, we all have a conversation with the patient, and then decide from there.

Question

Are there any side effects from being placed on ECMO?

Caitlin Demarest

Yes, a little bit of a complicated question. There are many risks, but if you're being offered ECMO, it means you're probably going to die without it. So generally, you know you don't have much of a choice, and if your transplant surgeon is offering you that, they can go through all those risks with you, and of course they would. I just put somebody on ECMO yesterday until they can get a lung transplant and we discussed all those risks. But generally most people and programs and doctors say, well, we're going to accept those risks because we're trying to save your life. And those programs that are going to offer it are generally very experienced, and so we're pretty good at doing it very safely, despite all the risks that come along with it.

Question

How do you go from being scared of transplant to not being scared? Are there any psychological supports in place, pre-transplant, to help?

Deborah Levine

I can start from our centre and then we can have other panellists from centres. The way to go from being scared to not being scared is education, learning early, learning the depths of what transplant is and what it isn't, and that would happen way before you even became a transplant candidate. I think that is how you learn now, at every program there are transplant psychiatrists, transplant social workers that are with us working as a team throughout the transplant process. Most of our patients do have some anxiety, some depression. They're being cared for by either transplant psychologists or psychiatrists or someone they've already been with. And I think that's very important. Because there's also a lot of, not just anxiety, but sometimes there's a lot of guilt. There's a lot of depression post-transplant. And these things really do need to be cared for, both by our team and our and our colleagues in in that field. So I think it's a wonderful question, and it's very, very real. And that's how most of us kind of go through that.

Reda Girgis

Maybe our patients can share their perspective on that. I'm sure that they were scared.

How did you come to grips with it and get to the point where you decided that this was the right thing for me, and I'm going to go forward.

Diane Ramirez

I was afraid of transplant. I think I was afraid of transplant up until the doctor came in and said, it's a go, and I was already in the operating room. You know that fear just kind of stays. You have to learn to live your life and get ready in spite of that fear of this big surgery. But I got to a point where I wanted to live.

Living on a high dose of oxygen, and still being symptomatic. Wearing 12 litres of oxygen, and being short of breath, was no longer good enough. I wanted to be able to go someplace or do things without this incredible limitation and the fear of making the decision and moving forward, that went away kind of organically. It just happened because I knew that this is what I had to do.

The centre that I went to does have a social worker and a psychologist and a psychiatrist that is available to everybody facing transplant whether you're on the list or not, and even after you've had the transplant. So having that support helped, and also there were other patients in rehab that were in the same position, and patient to patient support is always fantastic, and it just helped to be able to talk to them and just kind of get through it on a day-to-day basis. So that's how it worked for me.

Natalia Maeva

In my case I had no fear because the only solution in my case was the double lung transplantation. So for me there was a very big battle with Bulgarian authorities who in this period were able to change some legislation to be able to wait for the double lung transportation in my country in Bulgaria. And when the donor situation came, the hospital in Vienna sent a medical plane. So, it was a little bit like a joke. When I went to the plane I said to the two pilots, finally, I will fly like a millionaire. So I was joking all the time. Even though I was afraid, and I had my personal plane. The transplantation was okay, and when I woke up, the first thing that I did was that I started to look to my body and I saw that I have everything, and I was extremely happy.

Reda Girgis

Yeah, that's so important to hear. I learned from my surgeon. He always asked his recipients - What do they have to live for? And he finds that when patients have something important to live for, that they have a better attitude and a better outcome.

And so we heard from both these patients, how important their desire was to live longer and have a better quality of life, as we know, transplant has the potential to do that. And having that in your mind as something - Hey, this is what I need to do to achieve these goals. That can go a long way to dealing with that anxiety and the fear. But of course, it’s great to hear directly from the patients who are experiencing it, so thank you.

Question

I am a freelance software engineer, I work from home, and I have just a few clients in my home. I don't work over 40 hours a week and it is low stress. I'm very much enjoying my work and feel it's intellectually stimulating. My thinking is that doing some work would be good for my mental health. So with this in mind, would might be a reasonable timeframe to return to work?

Deborah Levine

What we're worried about at the beginning is really your interaction with a lot of people at the office, you could get sick, in getting there and getting home. And so my thought is, and all the other transplanters on the line can give their thoughts, is that I think I agree with you. In terms of being able to work a little bit from home it is good for you to get back into some of the normal states and I think as Dr Kolaitis said, it's definitely a risk benefit, but also it's definitely going to be individualised per patient and per their job.

Nicholas Kolaitis

I agree.

Question

Does the period spent on ECMO affect the memory of the lung transplant recipient.

Caitlin Demarest

Hard question to answer. Potentially, but there's no way to really know.

Deborah Levine

A lot of times after the transplant you're on very high doses of steroids and a lot of other medications. There are some changes neurologically from some of the immunosuppressants and going up and down on them. So it probably is multi-factorial if there are some changes in your memory and also in your thinking, especially right after transplant. So I think it could be a combination of everything.

Diane Ramirez

If I could just add something. The memory issue was something I was terrified of, because I've always had a really good memory and when they said your memory may change, I said no, that can't happen. And I talked to a couple of people, and I made it a point. I did my first crossword puzzle in ICU about 12 hours after I was extubated. And I make sure I do that kind of brain building stuff to keep my memory as sharp as I can. It's a side effect of the medication. There are things you can do as a patient to help with cognitive stuff, like practice writing puzzles, brain games. That kind of stuff that just kind of keeps the juices flowing to help as much as possible.

Question

Why did the mental health improvement only improve to the minimum level and not higher as was the case with other measures?

Nicholas Kolaitis

I think it's important to point out post-transplant as I mentioned, it's trading one disease for another, and some of the aspects that people can deal with after transplant are new concerns, or new issues. Sometimes after transplant, in addition to the recovery, you also have the new pill burden. Some patients will have some survivor guilt, the interactions with their family might be different than they were before, and so new mental health challenges do arise after transplant. So that might be why it's not as robust an improvement as some of the other measures, like the physical measures.

One of the things that we have been recommending more and more frequently for our transplant patients is to get a therapist, somebody external from their family and external from their transplant program that they can talk to about what they've been dealing with. Where they don't need to worry about mitigating the emotions of the therapist. They can just talk to them about their real concerns and everything that they've dealt with. Establishing a therapist before transplant is actually very helpful as well. If you can continue that relationship from before the transplant.

Deborah Levine

I agree with Dr Kolaitis. The other thing that I think one of speakers brought up, I don't know if it was Natalia or Diane, was patient advocacy and patient buddy systems. Those who've gone through transplants, those who are going through transplant, those who are going to go. It's very important that that kind of relationship continues. And then also family and caregiver support is so important both to mental and physical health post-transplant. Maybe one of the most important parts of our backup system is our patient's families, their friends, their colleagues, and other patients. So I think, along with the professional psychiatry, psychology, social workers, you have a whole backing, but I think also we can't forget some of the heroes or patients families who are there all the time at the hospital, bringing them to every appointment, or bringing them home after a bronchoscopy and again a big part of transplant for them as much as for you.

Question for Diane

What was your endurance prior to the transplant, and what is it now?

Diane

Right before the transplant at rehab I could walk 10-12 minutes on a high dose of oxygen without having to stop and rest. Prior to needing the transplant, years ago, I could walk miles without an issue. I'm back to walking miles without being short of breath, without needing any assistance. I exercise daily, I do Zumba a couple of times a week, I dance around the house and so my endurance is almost like it just keeps going. It takes a lot for me to get winded at this point. So I'm very active.

Reda Girgis

Thank you for clarifying that. Just from a clinical evidence basis, we know for a fact that people after a lung transplant have actually no cardiac or respiratory limitation to their exercise, so that they have normal function. Which is actually a myth that we'd like to dispel even amongst physicians. If one of our patients needs surgery for an unrelated problem, and they see that the patient's a lung transplant recipient, they say Oh my God, you know we can't do it. A lung transplant recipient with normal lung function has normal gas exchange and absolutely normal respiratory. So there's no limitations. But oftentimes, if we do a formal cardiopulmonary exercise test and measure, for example, their maximal oxygen consumption, they will be abnormal. But it's not because of limitations in heart or lung function. It's because of deconditioning, and some of that is from the medications that we use. But as I think Diane and Natalia have both alluded to, the rehabilitation reverses that problem and gets your muscles in proper conditioning. So important to do that before transplant. And you're going to be limited because of the heart and lungs at that point. But after transplant those won't be limiting things, it's going to be the muscles that limit you. And that can be for the most part reversed with good cardiopulmonary rehab, and staying in it indefinitely for life.

Closing remarks

Well, that's great. This was such a wonderful session. I really have to say, this is the best webinar I've ever participated in. And it was so informative, and I hope that everyone in the audience got something out of it, and we look forward to working on this issue further, to get the message out that lung transplantation is a good option for patients with PH.

Think about it early, and prepare for it, if need be.

Speakers & moderators

Other materials on this topic

More from IDDI Workstream and Task Force Learning

Our IDDI Workstreams & Task Forces are actively finding practical solutions to the key challenges facing Pulmonary Hypertension (PH) physicians, academics, industry, and regulators; raising awareness of Pulmonary Vascular Disease (PVD); and addressing key challenges in its causes, effects, and treatment.