Digital Clinic Knowledge Base

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) means high blood pressure in the lungs. This condition leads to pulmonary vascular disease (PVD), or peripheral arterial disease (PAD): the progressive obstruction of the lung blood vessels, which results in increasing shortness of breath and severe heart failure. This disease is incurable and often fatal. It can affect people of all ages, races and socio-economics groups; it can be seen in babies born with septal defects (a hole in their heart) and those living at high altitude.

The PH Digital Clinic Knowledge Base is a comprehensive centralised resource of terms, tools and tests used to aid the diagnosis of PH. Click on each term to learn more.

The blood gases in pulmonary arterial hypertension at rest show a normal or near-normal PaO2 but a low PaCO2 and a low HCO3-. In pulmonary hypertension due to lung disease PaO2 at rest is frequently low. Marked desaturation during exercise or at night is common in all forms of pulmonary hypertension.

Links to further reading

- Hoeper MM, Pletz MW, Golpon H, Welte T. Prognostic value of blood gas analyses in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2007;29:944–950.

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 67–119

- Peacock et al. Chapter 9. Clinical Features. In Pulmonary Circulation. Diseases and their Treatment Ed Peacock et al. 2016. 105-123

- Olsson RM et al. Capillary pCO2 helps distinguishing idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension from pulmonary hypertension due to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Respiratory Research 2015; 16: 34

The blood results in a patient with PAH can point to a number of particular causes.

- Full blood count. This can show an elevated haemoglobin secondary to hypoxaemia especially in congenital heart disease. It can also be elevated in myeloproliferative disorders which can be a marker of Jak2 positive myeloproliferative disorder. Anaemia can result in elevated cardiac output which can cause elevated pulmonary artery pressures.The platelet count can be low in patients who have splenomegaly in portopulmonary hypertension.

- Urea and electrolytes. A low sodium level has been implicated as a prognostic marker in PAH. Patients with chronic renal failure can have PH for a number of reasons including left heart dysfunction, anaemia and PAH (Group 5)

- Liver function. These can be abnormal in patients with portopulmonary hypertension and cirrhosis. These results are important when considering treatments for PAH which might have liver toxicity.

- Thyroid function: These can be abnormal and there is a strong association between autoimmune thyroid disease and that of idiopathic PAH.

- Autoimmune screen: There is a strong association of PAH with limited cutaneous sclerosis (anti-centromere positive), mixed connective tissue disease (anti-Ro/La positive) and lupus (anti-double stranded DNA positive). Less commonly are links with rheumatoid arthritis and large vessel vasculitis.

- Virology screen: There is an association with hepatitis C and PAH, but both hepatitis B and C can cause liver disease and portal hypertension can lead to portopulmonary hypertension.

- NT-proBNP: This is a surrogate marker of cardiac function and is elevated in PAH.

Links to further reading

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 16

- Monahan K et al. Reproducibility of intracardiac and transpulmonary biomarkers in the evaluation of pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary circulation 2013;3: 345-9

- Curnock et al. High prevalence of hypothyroidism in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Md Sci 1999;318:289

- Forfia et al. Hyponatremia Predicts Right Heart Failure and Poor Survival in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Am J Resp Crit Care 2008 177: 1364

The right heart catheterisation (RHC) is the gold standard diagnostic test to confirm pulmonary hypertension. This allows direct measurement of the pulmonary artery pressures and indirect measure of the left atrial pressure. Pressure readings should be determined at the end of normal expiration. The manometer should be set at position of the LA which is normally the midthoracic level with the patient supine. The PAWP is the best determinant of the LA pressure but can be misleading and in some cases a left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) is required. Vasoreactivity testing should be performed in patients suspected of having IPAH. This is usually performed with inhaled nitric oxide. Cardiac output can be determined most commonly by the thermodilution or Fick methods. A mixed venous oxygen saturation taken from the pulmonary artery should be measured in all cases and is a useful indicator of cardiac function and tissue delivery of oxygen. Other measurements which can be obtained at RHC include a saturation run which is used to investigate for left to right intracardiac shunts.

The RHC is usually performed at rest with patient supine but patients can be exercised on the table to give a good idea of pulmonary vascular responses to exercise.

Links to further reading

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 16

- Zuckerman et al. Safety of cardiac catheterisation at a centre specialising in the care of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ 2013 ; 3: 831

- Hoeper MM et al. Determination of cardiac output by Fick method, thermodilution and acetylene rebreathing in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:535

- Kovacs et al. Reading pulmonary vascular tracings. Am JResp Crit Care Med 2014; 252:257

- Kelly and Rabbani; Pulmonary-Artery Catheterization video ;N Engl J Med 2013; 369:e35December 19, 2013

- T. Kashour: Cardiac Catheterization Investigation of the Pulmonary Hypertensive Adult Patient (links to a page on our website – info copied below) T. Kashour: Cardiac Catheterization Investigation of the Pulmonary Hypertensive Adult Patient All credits to Dr. T. Kashour FPVRI, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Cardiac MRI is a non-invasive test which is extremely useful for the diagnosis of PAH and in the follow up and response to treatment. The disadvantages are that it cannot be used in patients with MR incompatible devices (pacemakers) and patients may not tolerate it due to claustrophobia. However it is an excellent imaging tool for RV assessment of function, size and morphology. It can determine stroke volume and cardiac outputs and can be used to assess for congenital heart abnormalities.

Links to further reading

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 16

- Peacock et al Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2013;22:526-534

- Peacock et al. Changes in right ventricular function measured by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients receiving PAH targeted therapy – EURO-MR study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:107-114

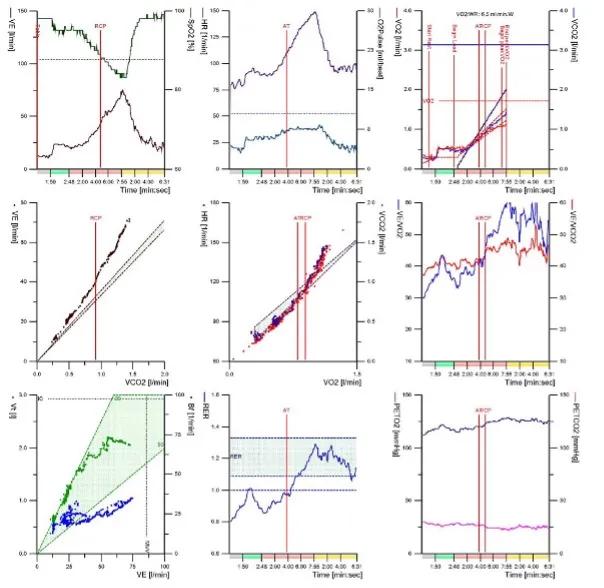

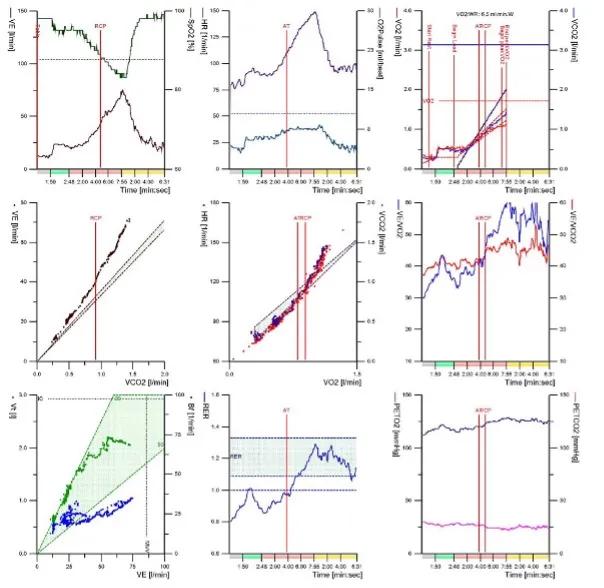

In a subject with PAH, the cardiopulmonary exercise test usually shows the following features

- Reduced peak exercise capacity (VO2)

- Impaired oxygen transport / delivery demonstrated by low VO2 at AT, steep HR-VO2 slope, low VO2-WR slope and low peak oxygen pulse

- Abnormal gas exchange shown by high ventilatory equivalents (VE/VCO2 & VE/VO2) at AT, high VE/VCO2 gradient, low PetCO2,desaturation and, if arterial blood gas is sampled, a high Aa gradient and high Vd/Vt ratio.

- Ventilatory reserve is normally preserved

Glossary

- VO2 – oxygen consumption

- VCO2 – carbon dioxide production

- VE - ventilation

- AT – anaerobic threshold

- HR – heart rate

- WR – workrate

- PetCO2 – end-tidal PCO2

- Aa gradient – alveolar – arterial gradient

- Vd/Vt ratio – dead space to tidal volume ratio

Figure 1. Typical nine panel plot in a patient with IPAH

Links to further reading

- Wensel R, Opitz CF, Anker SD, Winkler J, Hoffken G, Kleber FX, Sharma R, Hummel M, Hetzer R, Ewert R. Assessment of survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: importance of cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Circulation 2002;106:319–324.

- Sun XG, Hansen JE, Oudiz RJ,Wasserman K. Exercise pathophysiology in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2001;104:429–435.

- Wensel R, Francis DP, Meyer FJ, Opitz CF, Bruch L, Halank M, Winkler J, Seyfarth HJ, Glaser S, Blumberg F, Obst A, Dandel M, Hetzer R, Ewert R. Incremental prognostic value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing and resting haemodynamics in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:1193–1198.

- Arena R, Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Myers J, Guazzi M. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: an evidence-based review. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010;29:159–173.

- Johnson MK and Thomson S. The Role of Exercise Testing in the Modern Management of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Diseases 2014; 2: 120-147.

- Stephen Thomson - Oxygen uptake efficiency slope is a valid submaximal measure of exercise performance in pre capillary pulmonary hypertension

- Robert Naeije - Right heart afterload and exercise

- Robert Naejie - Assessing functional capacity in adults

- David Systrom - Why do we get short of breath with exercise?

The chest x-ray is abnormal in 90% of people with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) at the time of diagnosis. Typical changes include enlarged pulmonary arteries with peripheral pruning of vessels and cardiomegaly. There may be changes suggesting an alternative cause of pulmonary hypertension such as lung disease or pulmonary venous congestion.

Figure 1. Typical chest X-ray in IPAH

Links to further reading

- Rich et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension. A national prospective study. Annals of Internal Medicine 1987; 107:216-223

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 67–119

- Sproule, M. Chapter 8. Imaging. In Pulmonary Circulation. Diseases and their Treatment Ed Peacock et al. 2016. 138-152

- Ryan JR et al. The WHO classification of pulmonary hypertension: A case-based imaging compendium. Pulmonary Circulation 2012; 2:107-121

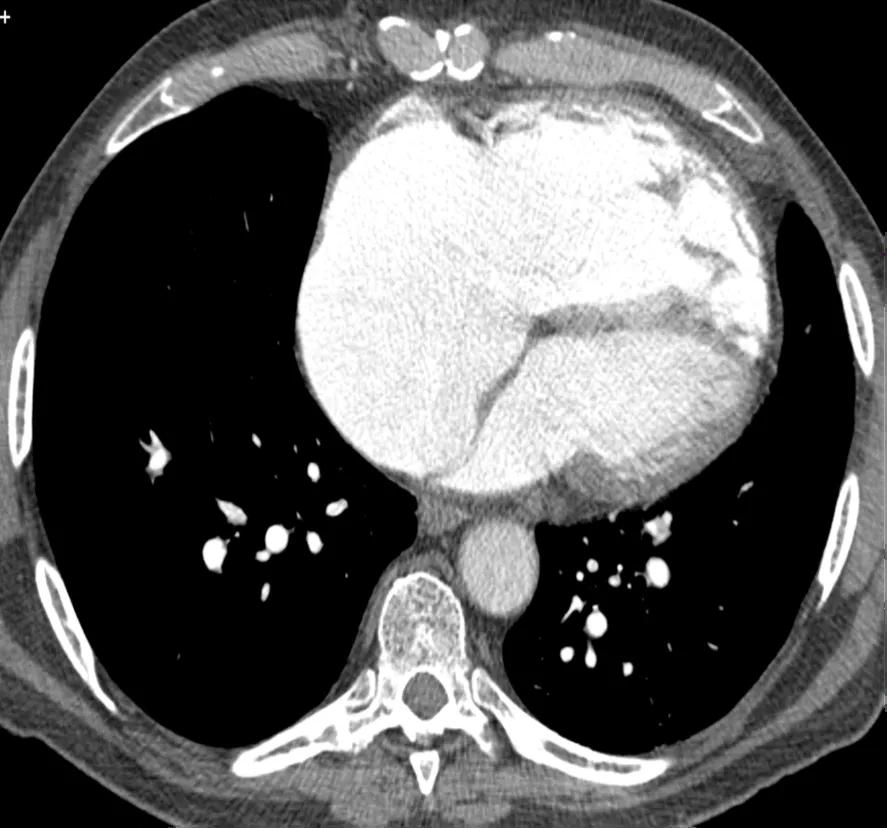

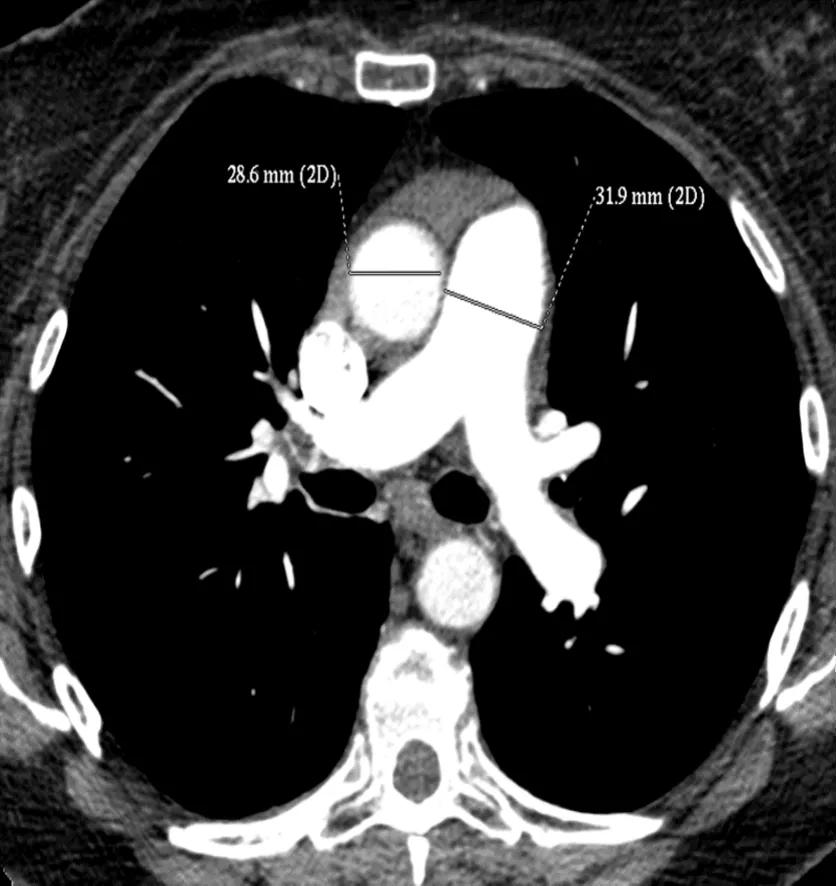

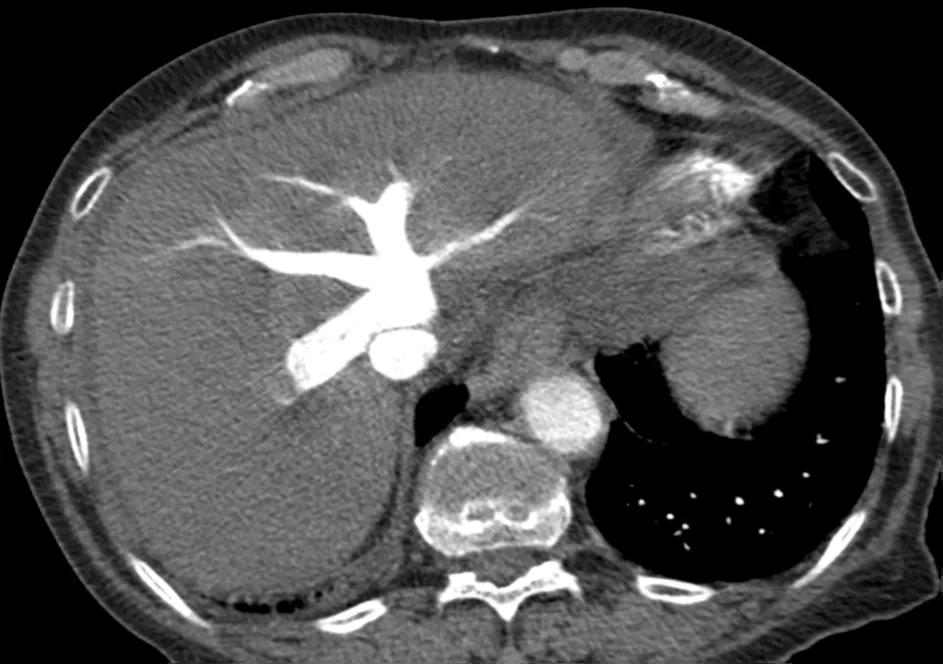

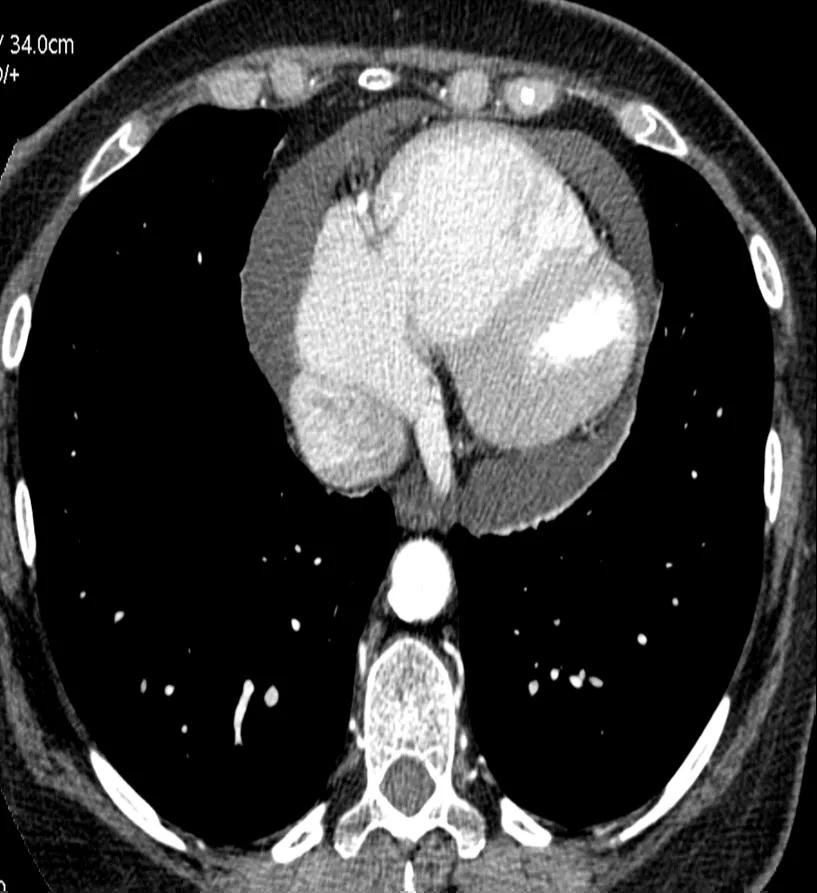

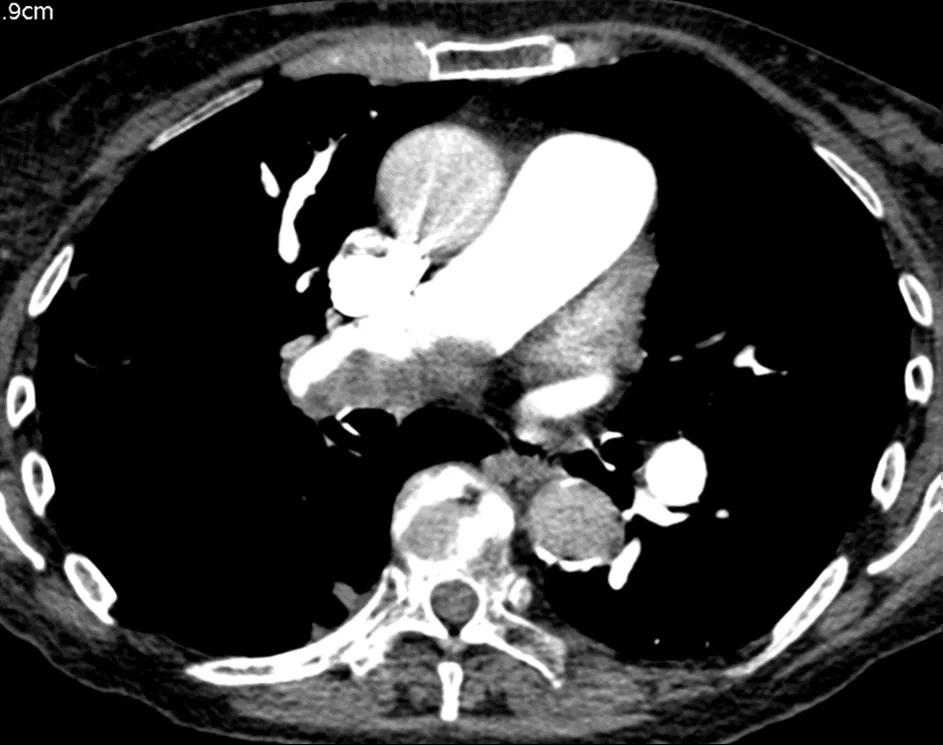

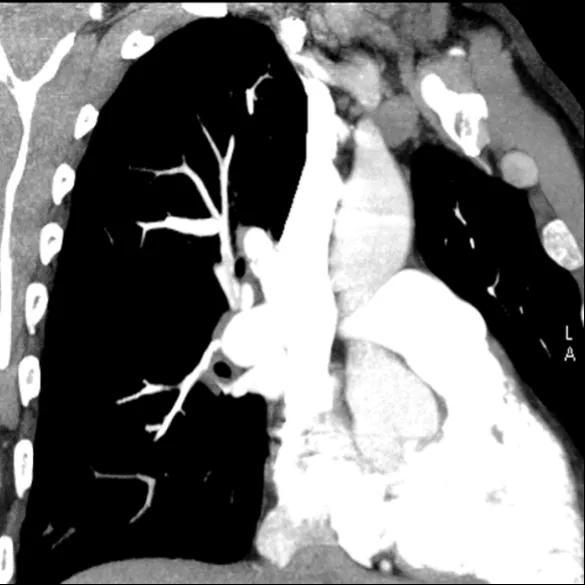

The CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) can suggest the presence of PH by morphological changes such as right heart enlargement, increased pulmonary artery (PA) diameter – relative to the aorta – the presence of significant tricuspid regurgitation and a pericardial effusion. It is useful in defining surgically treatable chronic thromboembolic disease, by showing features such as eccentric laminated thrombus, vessel amputation, webs, irregular vessels and bronchial artery dilatation.

Figure 1. CT pulmonary angiogram showing right heart enlargement

Figure 2. CTPA showing increased diameter of the pulmonary artery

Figure 3. CTPA showing tricuspid regurgitation

Figure 4. CTPA showing a pericardial effusion

Figure 5. CTPA showing eccentric laminated thrombus

Figure 6. CTPA showing irregular vessels

Figure 7. CTPA showing a web

Figure 8. CTPA showing bronchial artery dilation

Figure 9. CT pulmonary angiogram showing mosaicism

Images courtesy of Dr M Sproule, Scottish Pulmonary Vascular Unit

Links to further reading

- Rajaram S, Swift AJ, Condliffe R, Johns C, Elliot CA, Hill C, Davies C, Hurdman J,Sabroe I, Wild JM, Kiely DG. CT features of pulmonary arterial hypertension and its major subtypes: a systematic CT evaluation of 292 patients from the ASPIRE Registry. Thorax 2015;70:382–387.

- Heinrich M et al. CT findings in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: predictors of haemodynamic improvement after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Chest 2005; 127:1606-13

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 67–119

- Sproule, M. Chapter 8. Imaging. In Pulmonary Circulation. Diseases and their Treatment Ed Peacock et al. 2016. 138-152

- Auger WR et al. Evaluation of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension for pulmonary endarterectomy. Pulmonary Circulation 2012; 2: 155-162.

The ECG is often but not always abnormal in pulmonary arterial hypertension. The most sensitive feature is RV strain (ST depression and T wave inversion in leads V1 to V3). Other changes found include right axis deviation, P pulmonale, right bundle branch block, tall R waves especially anteriorly and prolonged QTc.

Links to further reading

- Rich et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension. A national prospective study. Annals of Internal Medicine 1987; 107:216-223

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 67–119

- Peacock et al. Chapter 9. Clinical Features. in Pulmonary Circulation: Diseases and their Treatment, Ed Peacock et al. 2016 pg105-123

- Bondermann D et al. A non-invasive algorithm to exclude pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension. ERJ 2011; 37:1096-1103

- Quantitative Estimation of Right Ventricular Hypertrophy using ECG Criteria in Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension: A Comparison with Cardiac MRI

The echocardiogram is probably the most important non-invasive test in the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension as it will often be the investigation which will decide on further diagnostic tests for the patient. It is important to remember that although this is an important test it is not the gold standard diagnostic test for PAH. That remains the right heart catheterisation. The important measurements in the echo focus on the pulmonary artery pressure (measured by tricuspid regurgitant velocity or pressure gradient) and the RV morphology. Key parameters include the RV dimensions and RV function.

Occasionally the TRV cannot be accurately measured and in these circumstances other parameters which may indicate PAH should be assessed. These include RV morphology and pulmonary artery acceleration time. In addition echo parameters such as Tricuspid annular planar systolic excursion(TAPSE) can be used to aid in patient prognosis.

Echo can also be used to assess the underlying cause of the pulmonary hypertension. For example an enlarged LA can indicate heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and an assessment of valvular function can indicate mitral regurgitation or aortic stenosis.

In patients with hypoxaemia, an assessment using agitated saline should be made to investigate the presence of a significant right to left intracardiac shunt.

Links to further reading

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 13

- Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK,Schiller NB. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registeredbranch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010; 23: 685–713.

- Forfia et al. Tricuspid annular planar systolic excursion predicts survival in pulmonary hypertension.A J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:1034

- Stefano Ghio - Echocardiography can replace RHC for RV assessment PRO

The signs due to pulmonary hypertension are subtle and include right ventricular heave, loud split P2, a right third or fourth heart sound and an early diastolic murmur due to pulmonary regurgitation. Signs due to right ventricular failure are more easily discerned such as an elevated JVP, pansystolic murmur of tricuspid regurgitation, peripheral oedema and ascites. Auscultation of the lungs is usually normal. There may also be signs of an underlying condition predisposing to pulmonary hypertension.

Links to further reading

- Rich et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension. A national prospective study. Annals of Internal Medicine 1987; 107:216-223

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 67–119

- Peacock et al. Chapter 9. Clinical Features. In Pulmonary Circulation. Diseases and their Treatment Ed Peacock et al. 2016 pg105-123

- Colman R et al. Utility of the physical examination in detecting pulmonary hypertension. A mixed methods study. Plos ONE 2014; 9:e108499

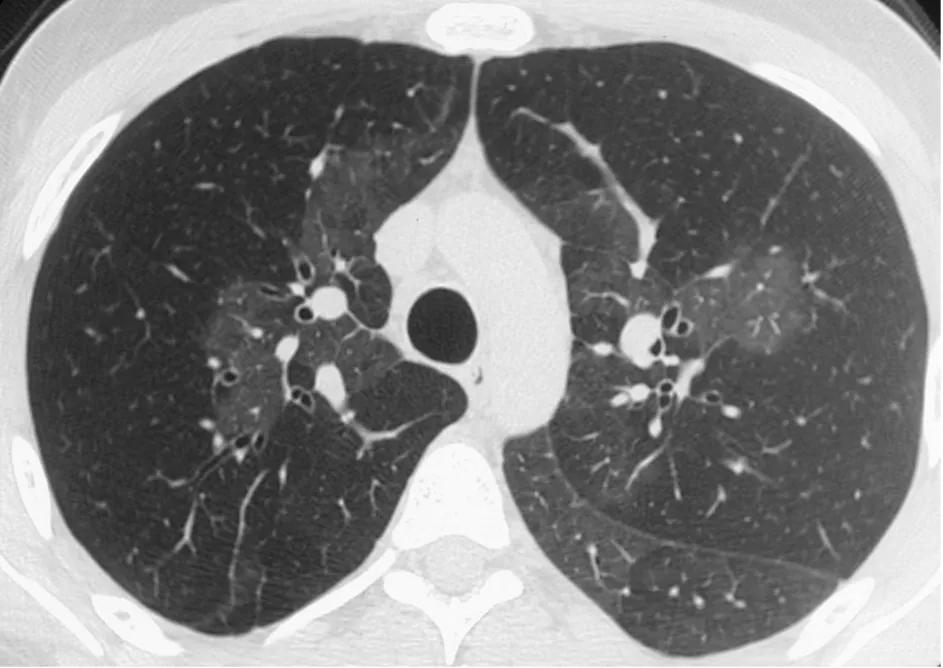

High resolution CT scans of the thorax are important to exclude the presence of parenchymal lung disease such as emphysema or interstitial lung disease. They may also lead to specific PH diagnoses such as pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) [thickened interlobular septa, lymphadenopathy, pleural effusions and centrilobular ground glass nodules] or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) [mosaicism and peripheral parenchymal opacities]. Ground glass changes are also seen in some people with PAH.

Figure 1. HRCT showing thickened interlobular septa in PVOD

The symptoms of PH arise primarily from right ventricular dysfunction and right ventricular failure. The commonest symptom is shortness of breath on exertion. Other symptoms include fatigue, exertional dizziness, collapse or chest pain, palpitations and ankle swelling. Cough is often a feature suggesting significant pulmonary arterial or right atrial enlargement. The mechanism is believed to be compression of a bronchus by the enlarging vessel/atrium.

Links to further reading

- Rich et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension. A national prospective study. Annals of Internal Medicine 1987; 107:216-223

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 67–119

- Peacock et al. Chapter 9. Clinical Features. In Pulmonary Circulation. Diseases and their Treatment Ed Peacock et al. 2016. 105-123

- Strange et al. Time from symptoms to definitive diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: The delay study. Pulmonary Circulation 2013; 3 : 89 - 94

The role of pulmonary function tests in pulmonary hypertension is to identify airway or parenchymal lung disease. In pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) there may be mild to moderate reduction in lung volumes and occasionally mild airflow obstruction, particularly at the peripheral level. Most people with PAH have decreased transfer factor.

Figure 1. Typical pulmonary function tests in IPAH

Further Reading

- Sun XG, Hansen JE, Oudiz RJ,Wasserman K. Pulmonary function in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1028–1035.

- Meyer FJ et al. Peripheral airway obstruction in primary pulmonary hypertension. Thorax 2002; 57:473-6

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 67–119

- Peacock et al. Chapter 9. Clinical Features. In Pulmonary Circulation : Diseases and their Treatment Ed Peacock et al. 2016. 105-123

- Exploring the Structural Basis for Pulmonary Gas Exchange, Edwald R. Weibel, M.D.

New medication and breakthroughs in science mean that the life expectancy of those living with pulmonary hypertension is much longer than it once was. Despite being discovered in 1891, there were no treatments for the disease for over 100 years, until 1994 when Flolan was introduced. Since then, there has been significant development, with multiple treatments now available. Due to these new treatments, the average life expectancy for someone with PH is over 7 years, and often more than 10 years.

PH is a progressive disease, meaning it advances in some much faster than in others, therefore, the life expectancy is varied from patient to patient. Without the appropriate treatment and management, PH life expectancy would be considerably shorter – around 30 months from diagnosis to death. However, constantly improving treatments and numerous centres across the UK and globally, mean this no longer needs to be the case. Additionally, it is becoming easier to diagnose the disease at an early stage, so this means it is possible to manage the symptoms for longer.

Managing the disease through lifestyle changes or treatment is possible, but sometimes the disease can lead to heart failure which can be life threatening. The overall outlook for someone living with PH can vary due to a number of things. These include:

- How severe your PH is

- Associated conditions

- Overall general health

- Your lifestyle

- Response to treatments

In the most serious of cases, a heart and lung transplant can be considered. A transplant comes with various risks, but is sometimes the only option for a patient who is unable to live with their current heart or lungs and medical or lifestyle therapy is no longer effective. In some of these cases, the transplant can both improve the quality of life and prolong the life expectancy. Unfortunately, due to the complications and risks associated with the transplant, some do not experience the full benefits.

Life expectancy and treating pulmonary hypertension

The cause of the pulmonary hypertension in each patient must be determined before deciding on a treatment. Often, PH is associated with another health condition, so treatment would need to include both PH and the underlying condition. Without treatment, the life expectancy of someone living with pulmonary hypertension would be considerably shorter, and quality of life may be worse. Increasingly, the importance of exercise and living a healthy lifestyle is highlighted by health professionals when it comes to improving quality of life and increasing life expectancy in PH.

Cure for pulmonary hypertension

Unfortunately, there is still no known cure for pulmonary hypertension, only ways of improving life quality and prolonging life expectancy. However, there is now significant research going into new medication to treat PH. Also, many clinical trials are taking place, so doctors remain hopeful that quality of life and average life expectancy will continue to improve for patients living with pulmonary hypertension. It is possible for a PH patient to live a long life with few restrictions, provided it is recognised early and managed correctly. However, this varies entirely from patient to patient. Some may experience slow symptom progression, but for other patients progression may happen more rapidly.

Early diagnosis

There is no doubt that the best way of managing PH and prolonging a patient's life expectancy is through early diagnosis. Vastly improved diagnostic techniques over recent years have resulted in many patients getting a quicker and more accurate diagnosis. Therefore, the patient can be treated at the beginning of the disease, before it has moved into later and more serious stages. Subsequently this can drastically improve not only the life expectancy, but also the quality of life of the patient. For example, a study observing more than 1,000 patients in Taiwan with PH, determined that 62.6% of patients are now surviving 10 years or more following their pulmonary hypertension diagnosis. If the pulmonary hypertension is caused by another condition, then said condition should be treated primarily. This may prevent the pulmonary arteries being permanently damaged. Frequent monitoring of the progression of symptoms is also important. This can be done through various tests, such as the six minute walk test. The sooner new symptoms are detected through testing, the sooner they can be treated.

Outlook and prognosis

The overall outlook and prognosis of a PH patient is entirely dependent on variables such as:

- the cause of the PH

- how quickly it is diagnosed

- how advanced your symptoms are

- whether you have another underlying health condition

- your general health and lifestyle

Therefore, early diagnosis, correct treatment and a healthy lifestyle are the best ways of managing PH and increasing life expectancy.

Pulmonary embolisms occur as a blockage in one of the arteries in the lungs. In a predominant amount of cases, an embolism in the lung arteries is caused by blood clots that originate from deep veins in the legs and in some cases other parts of the body.

As a result of these clots flowing to the lungs, pulmonary embolisms can be fatal. There are various measures able to help reduce the likelihood of a pulmonary embolism, however early diagnosis and consequent therapy are the most important factors in severely reducing risk of death.

Shared symptoms of pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary embolism

Symptoms of both pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary embolism can vary greatly, depending on the size of the clots, the affected arteries, and whether you have any underlying disease. Shared symptoms can include:

- Lightheadedness or dizziness

- Swelling (edema) in your ankles, legs and eventually in your abdomen (ascites)

- Clammy or discolored skin (cyanosis)

- Chest pressure or pain

- Racing pulse or heart palpitations

Differences between pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolisms are characterised as an acute illness and pulmonary hypertension is a chronic illness. Acute illnesses generally develop suddenly and last a short time, often only a few days or weeks. Chronic conditions develop slowly and may worsen over an extended period of time months to years.

Pulmonary embolisms can be life-threatening. About one-third of people with undiagnosed and untreated pulmonary embolism don't survive. When the condition is diagnosed and treated promptly, however, that number drops dramatically. Pulmonary embolism can also lead to pulmonary hypertension, a condition in which the blood pressure in your lungs and in the right side of the heart is too high. When you have obstructions in the arteries inside your lungs, your heart must work harder to push blood through those vessels, which increases blood pressure and eventually weakens your heart.

In rare cases, small emboli occur frequently and develop over time, resulting in chronic pulmonary hypertension, also known as chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

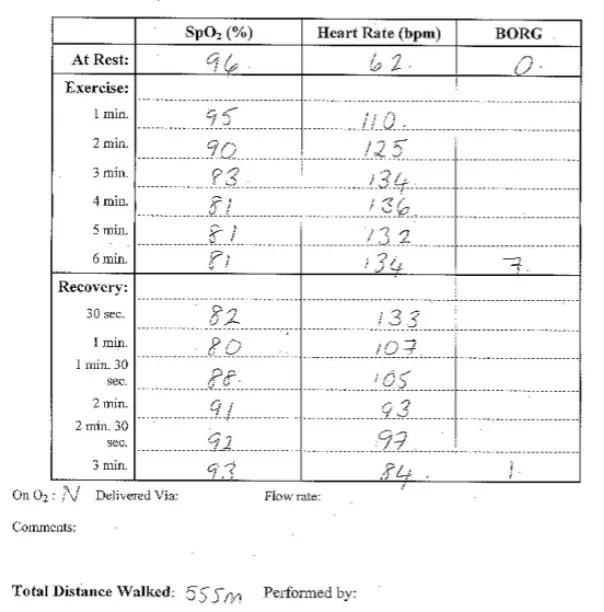

The 6MWT is a critical submaximal exercise test in the assessment of PAH. The absolute distance achieved at baseline has been associated with prognosis and the test can be used to assess for response to treatment. It has been long established as a key outcome in clinical drug trials. The important feature in the walk is to ensure that it has been carried out in accordance with the ATS recommendations. Furthermore it is important to note if the test has been performed on oxygen, that the heart rate rises to ensure the patient has exerted themselves and in PAH desaturation occurs.

Figure 1. Six minute walk test in patient with IPAH

Links to further reading

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 22

- Nickel N, Golpon H, Greer M, Knudsen L, Olsson K, Westerkamp V, Welte T, Hoeper MM. The prognostic impact of follow-up assessments in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2012;39: 589–596.

- ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test.Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Jul 1;166(1):111-7.

- Group II Part III: R. Oudiz: 6MW test

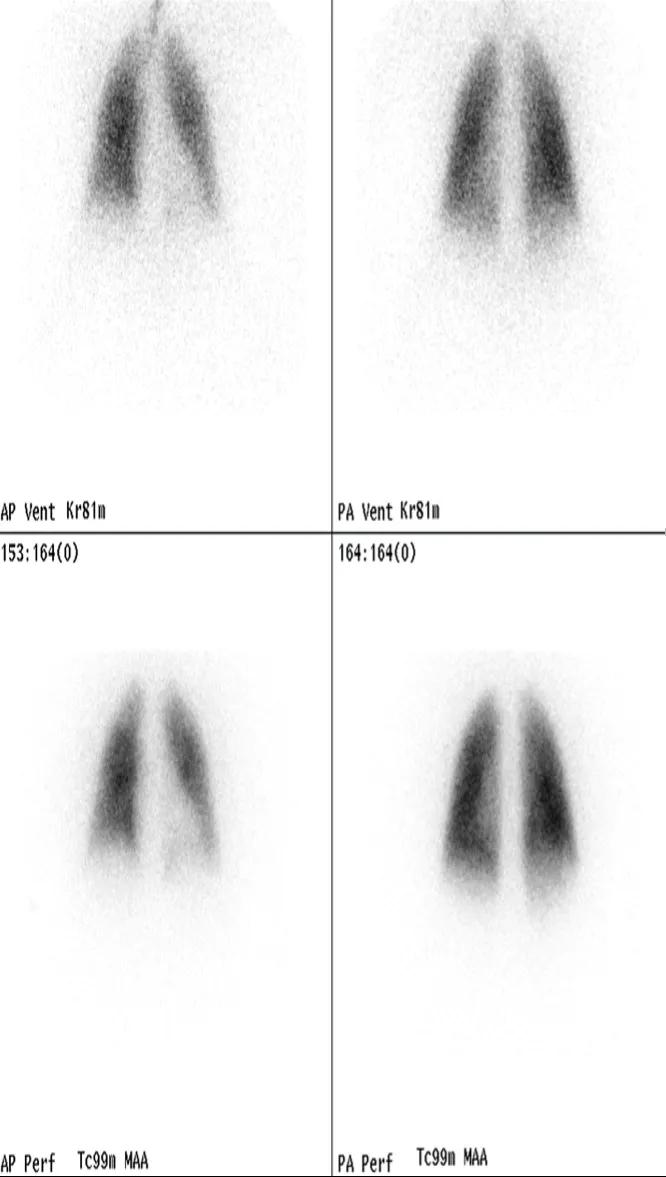

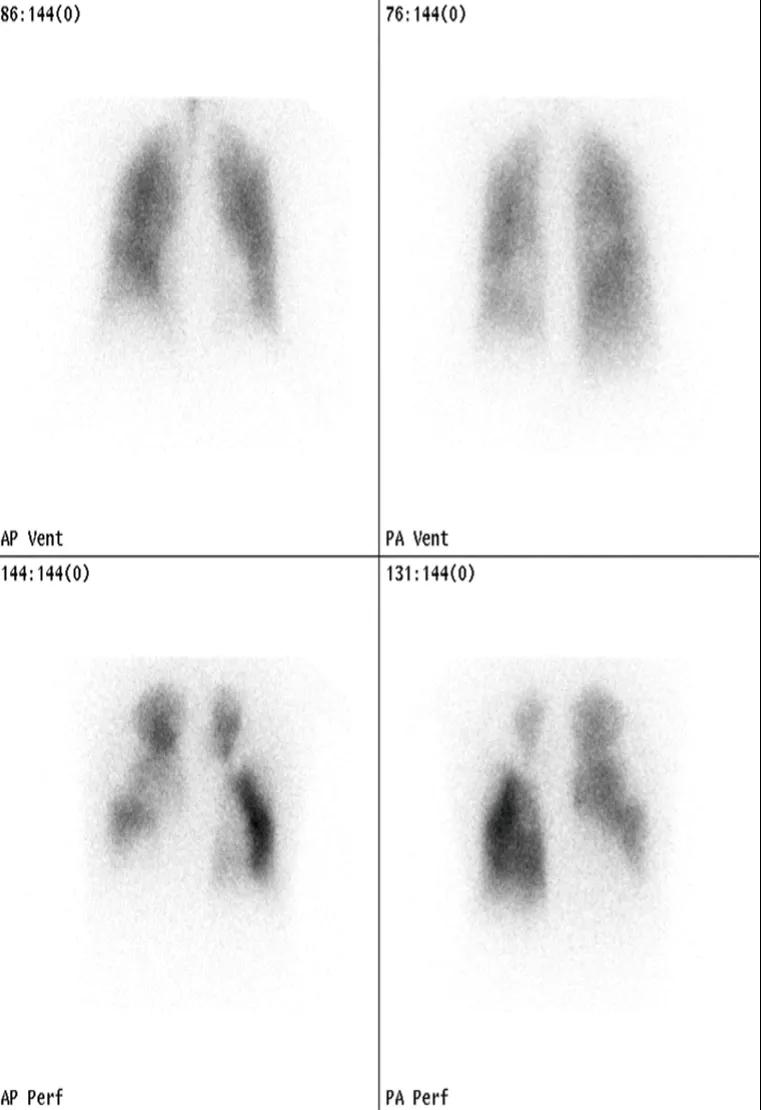

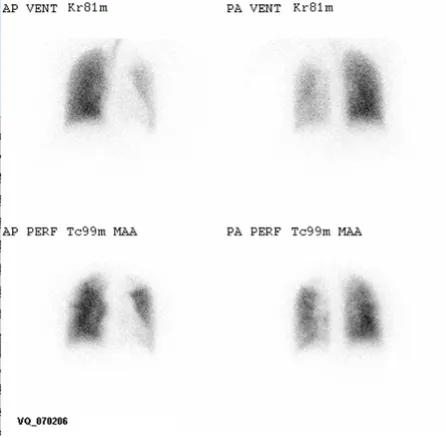

A ventilation/perfusion lung scan should be performed in patients with pulmonary hypertension because it has the highest sensitivity for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). A normal or low probability scan can exclude CTEPH with a sensitivity and specificity both greater than 90%.

Figure 1. VQ scan in normal subject

Figure 2. VQ scan in CTEPH

Figure 3. VQ scan in IPAH

Links to further reading

- Tunariu N, Gibbs SJR, Win Z, Gin-Sing W, Graham A, Gishen P, AL-Nahhas A.Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy Is more sensitive than multidetector CTPA in detecting chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease as a treatable cause of pulmonary hypertension. J Nucl Med 2007;48:680–684.

- The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. European Heart Journal (2016) 37, 67–119

- Sproule, M. Chapter 8. Imaging. In Pulmonary Circulation. Diseases and their Treatment Ed Peacock et al. 2016. 138-152

- Auger WR et al. Evaluation of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension for pulmonary endarterectomy. Pulmonary Circulation 2012; 2: 155-162.